FRIEND OF THE PEOPLE - ACCOUNTS FROM VARIED SOURCES

Following John Collins' liberation from Warwick Gaol in July 1840, he was enthusiastically welcomed in his home town of Birmingham as well as other important towns in England and Scotland. Collins and other recently released Chartist leaders helped revive the flagging reform movement.

Below are accounts of events about Collins and a smattering of his speeches from contemporary sources. (I have inserted additional paragraphs to facilitate ease of reading.)

Below are accounts of events about Collins and a smattering of his speeches from contemporary sources. (I have inserted additional paragraphs to facilitate ease of reading.)

1. History of the Chartist Movement, Robert Gammage

2. Report by the Birmingham Police, National Archives

3. Northern Star 22 August 1840

4. Birmingham Complete Suffrage Union, An Extract from the Proceedings 5 April 1842

2. Report by the Birmingham Police, National Archives

3. Northern Star 22 August 1840

4. Birmingham Complete Suffrage Union, An Extract from the Proceedings 5 April 1842

1. "HISTORY OF THE CHARTIST MOVEMENT" - ROBERT GAMMAGE

In Chapter IX, Gammage wrote an account of Collins' release from Warwick Gaol, and the receptions at Birmingham and London:

In Chapter IX, Gammage wrote an account of Collins' release from Warwick Gaol, and the receptions at Birmingham and London:

|

Birmingham

"But events were now about to occur, which were calculated to re-kindle the old fire of the Chartist movement. The time of imprisonment of some of the leaders had expired, and their release was looked forward to with much interest and expectancy. "On July the 24th, 1840, the doors of Warwick gaol were opened, and forth from their living tomb issued William Lovett and John Collins. The former had evidently suffered much from his confinement; he was considerably emaciated, and had some difficulty in walking unsupported. Collins appeared to have better resisted his treatment under prison discipline. The liberated victims, accompanied by a deputation, made their way to the house of Mr. French, where a breakfast had been provided. Thompson on behalf of the Birmingham Chartists, gave an invitation to Messrs. Lovett and Collins to a public entertainment in that town. |

"Collins accepted but Lovett, both on the grounds of ill health and prior engagements, declined with thanks the invitation. On the following day the Chartists of Warwick gave an entertainment in honour of the above gentlemen, which was attended by Collins. Cardo presided, and several speeches were made by Collins, Donaldson, and others. Songs were sung, and all passed off with great harmony and spirit. The Birmingham demonstration came off on Monday July the 27th, 1840, and was everything that might have been anticipated both in numbers and enthusiasm. A procession started at ten o'clock from the Cross Guns, Lancaster street, in the following order:-

"1st. — two marshals on horseback ; 2nd. — members of committee two abreast ; 3rd. — body of collectors and subscribers four abreast; 4th. — a large and appropriate banner; 5th. — union band in their uniform; 6th. — carriage drawn by fourgreys, containing Collins and family; 7th. — carriages with deputations from several parts of England and Scotland ; 8th. — carriages containing the committee of the Female Political Union ; 9th. — trades four abreast; 10th. — a large banner ; 11th. — a brass band ; I2th. — trades four abreast ; 13th. — friends from the surrounding districts four abreast ; I4th. — two marshals on horseback to bring up the general procession.

"1st. — two marshals on horseback ; 2nd. — members of committee two abreast ; 3rd. — body of collectors and subscribers four abreast; 4th. — a large and appropriate banner; 5th. — union band in their uniform; 6th. — carriage drawn by fourgreys, containing Collins and family; 7th. — carriages with deputations from several parts of England and Scotland ; 8th. — carriages containing the committee of the Female Political Union ; 9th. — trades four abreast; 10th. — a large banner ; 11th. — a brass band ; I2th. — trades four abreast ; 13th. — friends from the surrounding districts four abreast ; I4th. — two marshals on horseback to bring up the general procession.

"In the evening a banquet was given in honour of Collins, at which upwards of eight hundred persons sat down. Mr. Farebrother Page, town councillor, occupied the chair, and proposed the usual radical toasts and sentiments. Messrs. Cardo, Warden, Thomason, Thompson, Charlton, Greaves, and Watson responded ; and Collins, on his health being drank with three times three, acknowledged the compliment with an animated address.

"On the following morning there was a meeting of the delegates, who had been deputed to attend the demonstration. Messrs. Holman and Jackson attended from Totness, Leach from Manchester, Spurr from London, Messrs. Carter and Greaves from Oldham and Saddleworth, Chappel from Stock-port, Thomason from Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Chance from Stourbridge, Chadwick from the Potteries, Griffin from West Bromwich, Cook from Dudley, Lewis from Bristol, Morgan from Bath, Millson from Cheltenham, Sankey from Edinburgh, and O'Neil from Lanarkshire. On the motion of the London and Lanarkshire delegates, the following resolution was unanimously adopted:-

" 'That we, the delegates from various parts of England and Scotland, for the purpose of congratulating our friends, John Collins and William Lovett, on their liberation from prison, after considering the plan of organization adopted at the Manchester delegate meeting, which was assembled for that purpose, express our approval of the same and our determination to give it our most cordial support in our various localities.' Another out-door meeting was held in the evening, on a piece of ground purchased for a new People's Hall, which was addressed by Messrs. Chadwick, Chappel, Spurr, O'Neil, Empson, Smallwood, and Mumford; and an address previously adopted by the delegates was read to the meeting and carried unanimously, as were also various resolutions ; and thus ended the great Birmingham demonstration of the Chartists in honour of two of the foremost sufferers in their cause."

"On the following morning there was a meeting of the delegates, who had been deputed to attend the demonstration. Messrs. Holman and Jackson attended from Totness, Leach from Manchester, Spurr from London, Messrs. Carter and Greaves from Oldham and Saddleworth, Chappel from Stock-port, Thomason from Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Chance from Stourbridge, Chadwick from the Potteries, Griffin from West Bromwich, Cook from Dudley, Lewis from Bristol, Morgan from Bath, Millson from Cheltenham, Sankey from Edinburgh, and O'Neil from Lanarkshire. On the motion of the London and Lanarkshire delegates, the following resolution was unanimously adopted:-

" 'That we, the delegates from various parts of England and Scotland, for the purpose of congratulating our friends, John Collins and William Lovett, on their liberation from prison, after considering the plan of organization adopted at the Manchester delegate meeting, which was assembled for that purpose, express our approval of the same and our determination to give it our most cordial support in our various localities.' Another out-door meeting was held in the evening, on a piece of ground purchased for a new People's Hall, which was addressed by Messrs. Chadwick, Chappel, Spurr, O'Neil, Empson, Smallwood, and Mumford; and an address previously adopted by the delegates was read to the meeting and carried unanimously, as were also various resolutions ; and thus ended the great Birmingham demonstration of the Chartists in honour of two of the foremost sufferers in their cause."

London

"The Chartists of London, though in a more humble manner, testified their appreciation of the services of Lovett and Collins, by honouring them with a public dinner at White Conduit House, on Monday, August 3rd. The Chair was taken by Mr. Wakley, M. P., who was supported on his right by Lovett, and on his left by Collins. Mr. Duncombe, M.P., was also present. Wakley denounced strongly the treatment to which those gentlemen had been subjected. Lovett, on his health being proposed, made an able speech. The first paragraph will show whether his imprisonment had effected the object desired by his persecutors. 'Those who had not experienced the monotony and misery of a prison, could scarcely estimate how wholesome and refreshing were the grateful blessings of freedom. Notwithstanding these feelings, he would say, welcome once more the starving imprisonment of Warwick Gaol — welcome again all the misery he had suffered, rather than the right of public meetings should be questioned, and peaceful bodies of people dispersed by blue-coated bludgeon men, and not a voice be found to denounce the oppressor, and publish his infamy to the. world.'

"Collins spoke in a humorous strain, to the great delight of the meeting. Cleave introduced Messrs. Morling and Londsell, from Brighton, who presented an address from the Chartists of that fashionable town to Lovett and Collins; after which Duncombe addressed the assembly, entering into the facts of the Government persecution, which he cordially denounced. Mr. J. Watson and Dr. Epps, with several others, responded to various toasts and sentiments, after which the meeting separated, highly delighted with the evening's entertainment."

"The Chartists of London, though in a more humble manner, testified their appreciation of the services of Lovett and Collins, by honouring them with a public dinner at White Conduit House, on Monday, August 3rd. The Chair was taken by Mr. Wakley, M. P., who was supported on his right by Lovett, and on his left by Collins. Mr. Duncombe, M.P., was also present. Wakley denounced strongly the treatment to which those gentlemen had been subjected. Lovett, on his health being proposed, made an able speech. The first paragraph will show whether his imprisonment had effected the object desired by his persecutors. 'Those who had not experienced the monotony and misery of a prison, could scarcely estimate how wholesome and refreshing were the grateful blessings of freedom. Notwithstanding these feelings, he would say, welcome once more the starving imprisonment of Warwick Gaol — welcome again all the misery he had suffered, rather than the right of public meetings should be questioned, and peaceful bodies of people dispersed by blue-coated bludgeon men, and not a voice be found to denounce the oppressor, and publish his infamy to the. world.'

"Collins spoke in a humorous strain, to the great delight of the meeting. Cleave introduced Messrs. Morling and Londsell, from Brighton, who presented an address from the Chartists of that fashionable town to Lovett and Collins; after which Duncombe addressed the assembly, entering into the facts of the Government persecution, which he cordially denounced. Mr. J. Watson and Dr. Epps, with several others, responded to various toasts and sentiments, after which the meeting separated, highly delighted with the evening's entertainment."

2. BIRMINGHAM POLICE REPORT

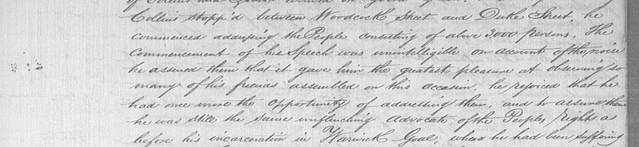

Report by Superintendent Ross of the Birmingham Police telling about Collins' arrival into Birmingham and his speech at Gosta Green.

Report by Superintendent Ross of the Birmingham Police telling about Collins' arrival into Birmingham and his speech at Gosta Green.

"Third Division

"28 July 1840

"Superintendent Ross begs most respectfully to report for the information of the Commissioner that at about 20 minutes before 2pm the procession of Collins arrived on Gosta Green, the carriage containing Collins stopped between Woodcock Street and Duke Street, he commenced addressing the people consisting of above 3,000 people. The commencement of his Speech was unintelligible on account of the noise, he assured them that it gave him the greatest pleasure at observing so many of his friends assembled on this occasion, he rejoiced that he had once more the opportunity of addressing them, and to assure them he was still the same unflinching advocate of the People's rights as before his incarceration in Warwick Gaol, where he had been suffering under the Tyranical persecution of as Weak and Imbecile a Whig Government as ever a Country was afflicted with, but he hoped and trusted they would never rest until they had wiped away so foul a stain from their Country.

"If the Government think that by prosecutions and by imprisonments that they will stop the tide of public opinion, they will find themselves most egregiously deceived, for he was himself as firmly devoted to the People's cause as ever and still willing to be sacrificed at the Alter of the Country for what my friends have suffered! I did but speak the truth and such I would repeat again; you all know it was the truth; I spoke nothing but the truth; I was arrested and punished for the truth and yet it is still the truth after all!

"I said then it was a Cruel, a Wanton and Bloodthirsty Attack by persons in power upon the Property and Person of the People of Birmingham. I repeat it now (here he repeated the words above). I would ask is this Town in a State Organization, if it is not it must be. No doubt to some it may appear that the prospect of success is farther from us now than it was 14 months since, but he hoped they would show by their actions that they are still sincere and alive to their rights, for his own part much as he had suffered from incarceration in Warwick Gaol he was still ready to suffer in the righteous cause, and to say to Warwick Walls and to all the privations he had suffered, Welcome back again!

"And now my friends, I have a few words to say to you respecting the Visiting Magistrates of the County of Warwick. I had occasion to make a written application for the letters which had been directed to me during my imprisonment. Not receiving an answer I went accompanied by my friend Mr Thompson and had an interview with the Governor, who in reply said that he could not deliver the Letters to me until he had received a communication from the Secretary of State. I enquired how long it would take him to receive an answer, he replied I shall not write at all, it is for you to write. Not me I said surely you cannot understand me, and requested to be shown into the room where five of the Visiting Magistrates were assembled. The Governor announced to them that I wished an interview accompanied by my friend. I was conducted upstairs, but judge my surprise when I was informed that I might have the interview but that my friend could not be admitted. Would this be believed in these enlightened times, in the Nineteenth Century that five Magistrates should be afraid of one poor working man with his friend, fearing no doubt that I might state something unpleasant to their feelings and that they might be provoked to say something in reply for which they might afterwards be sorry, or might perhaps wish to alter or put a different construction upon some word or other which I might utter for the purpose of suiting their own party purposes. And I have no hesitation in saying that many of them are capable of this. I of course declined the interview.

"He had to speak in the highest terms of the Gentlemanly conducted of [William] Collins Esq one of the Visiting Magistrates, and also to express thus publicly his grateful acknowledgement to Lord Brougham, Mr Wakely, Mr Fielding and others for the able manner in which they had introduced his Case to the House of Commons. and now he would read to them a Letter from Finality John - that Little Lord of great consequence, a Letter written by him officially during the time he held the Office of Secretary of State for the Home department (here he read the letter the content of which could not be heard) after reading which he again addressed them. Thus my friends you see I am accused of endeavouring to overturn the state of things by Anarchy & Bloodshed. You see I was indicted for one offence and punished for another.

"When after reading a letter from Sir Eardly Wilmot upon the conditions of the Labouring People and the condition of the Prisoners confined for misdemeanours he contrasted the one with the other, he would maintain that badly as they were fed, severe as was the prison discipline, the condition of the Prisoner is ever preferable to that of the English Labourer of the present day. He said he should shortly have an opportunity of submitting to them a New Plan of Organization in the course of a few days. Tickets would be issued and he hoped that they would show themselves sincere to their cause, after dwelling at some length, but which was not of an important nature the Meeting quietly dispersed about 1/2 P. 2 o'clock.

"Signed John Ross

"Superintendent"

"28 July 1840

"Superintendent Ross begs most respectfully to report for the information of the Commissioner that at about 20 minutes before 2pm the procession of Collins arrived on Gosta Green, the carriage containing Collins stopped between Woodcock Street and Duke Street, he commenced addressing the people consisting of above 3,000 people. The commencement of his Speech was unintelligible on account of the noise, he assured them that it gave him the greatest pleasure at observing so many of his friends assembled on this occasion, he rejoiced that he had once more the opportunity of addressing them, and to assure them he was still the same unflinching advocate of the People's rights as before his incarceration in Warwick Gaol, where he had been suffering under the Tyranical persecution of as Weak and Imbecile a Whig Government as ever a Country was afflicted with, but he hoped and trusted they would never rest until they had wiped away so foul a stain from their Country.

"If the Government think that by prosecutions and by imprisonments that they will stop the tide of public opinion, they will find themselves most egregiously deceived, for he was himself as firmly devoted to the People's cause as ever and still willing to be sacrificed at the Alter of the Country for what my friends have suffered! I did but speak the truth and such I would repeat again; you all know it was the truth; I spoke nothing but the truth; I was arrested and punished for the truth and yet it is still the truth after all!

"I said then it was a Cruel, a Wanton and Bloodthirsty Attack by persons in power upon the Property and Person of the People of Birmingham. I repeat it now (here he repeated the words above). I would ask is this Town in a State Organization, if it is not it must be. No doubt to some it may appear that the prospect of success is farther from us now than it was 14 months since, but he hoped they would show by their actions that they are still sincere and alive to their rights, for his own part much as he had suffered from incarceration in Warwick Gaol he was still ready to suffer in the righteous cause, and to say to Warwick Walls and to all the privations he had suffered, Welcome back again!

"And now my friends, I have a few words to say to you respecting the Visiting Magistrates of the County of Warwick. I had occasion to make a written application for the letters which had been directed to me during my imprisonment. Not receiving an answer I went accompanied by my friend Mr Thompson and had an interview with the Governor, who in reply said that he could not deliver the Letters to me until he had received a communication from the Secretary of State. I enquired how long it would take him to receive an answer, he replied I shall not write at all, it is for you to write. Not me I said surely you cannot understand me, and requested to be shown into the room where five of the Visiting Magistrates were assembled. The Governor announced to them that I wished an interview accompanied by my friend. I was conducted upstairs, but judge my surprise when I was informed that I might have the interview but that my friend could not be admitted. Would this be believed in these enlightened times, in the Nineteenth Century that five Magistrates should be afraid of one poor working man with his friend, fearing no doubt that I might state something unpleasant to their feelings and that they might be provoked to say something in reply for which they might afterwards be sorry, or might perhaps wish to alter or put a different construction upon some word or other which I might utter for the purpose of suiting their own party purposes. And I have no hesitation in saying that many of them are capable of this. I of course declined the interview.

"He had to speak in the highest terms of the Gentlemanly conducted of [William] Collins Esq one of the Visiting Magistrates, and also to express thus publicly his grateful acknowledgement to Lord Brougham, Mr Wakely, Mr Fielding and others for the able manner in which they had introduced his Case to the House of Commons. and now he would read to them a Letter from Finality John - that Little Lord of great consequence, a Letter written by him officially during the time he held the Office of Secretary of State for the Home department (here he read the letter the content of which could not be heard) after reading which he again addressed them. Thus my friends you see I am accused of endeavouring to overturn the state of things by Anarchy & Bloodshed. You see I was indicted for one offence and punished for another.

"When after reading a letter from Sir Eardly Wilmot upon the conditions of the Labouring People and the condition of the Prisoners confined for misdemeanours he contrasted the one with the other, he would maintain that badly as they were fed, severe as was the prison discipline, the condition of the Prisoner is ever preferable to that of the English Labourer of the present day. He said he should shortly have an opportunity of submitting to them a New Plan of Organization in the course of a few days. Tickets would be issued and he hoped that they would show themselves sincere to their cause, after dwelling at some length, but which was not of an important nature the Meeting quietly dispersed about 1/2 P. 2 o'clock.

"Signed John Ross

"Superintendent"

3. NORTHERN STAR & LEEDS GENERAL

|

The Chartist newspaper The Northern Star of August 22nd 1840 gave an account of a Manchester Rally in honor of the newly released champions of the people, Peter McDouall and John Collins. A procession of 2,000 including bands and flags accompanied the two men in an open carriage and four, with postillions in green and white liveries. The streets were lined with a "dense mass of human beings" as far as the eye could see, so that the procession could barely move on. On entering the Carpenters Hall (able to hold 3,000 comfortably) the applause for the distinguished patriots was "absolutely deafening." and the whole company rose to its feet. The following is Collins' speech, which he began with humorous remarks on a newspaper article he had read that morning.

|

The Carpenters Hall, Manchester

"THE CHAIRMAN [James Leech of Manchester] said it would now be his duty to introduce to them a man whom he had known and esteemed for some time; and who, he felt, had still greater claims on his respect since he had witnessed the manner in which he had been received by his fellow-townsmen at Birmingham after he came out of Warwick Gaol. He alluded to his friend, John Collins, who would now address them.

"THE CHAIRMAN [James Leech of Manchester] said it would now be his duty to introduce to them a man whom he had known and esteemed for some time; and who, he felt, had still greater claims on his respect since he had witnessed the manner in which he had been received by his fellow-townsmen at Birmingham after he came out of Warwick Gaol. He alluded to his friend, John Collins, who would now address them.

"MR COLLINS was received with the same lively marks of interest and favour which had greeted the appearance of Dr McDouall. He [Collins] addressed the meeting as fellow-slaves, and said he felt particularly proud of that opportunity of addressing the working men of Manchester. He had that morning been reading in one of the Manchester papers an article which was written with a very bitter feeling; so bitter as to be manifest in every line In that article the writer, in reference to those whom he called the 'poor Chartists,' stated that last week he witnessed the extension of mercy by Lord Normanby [Secretary of State] to the Glasgow cotton-spinners; that this week McDouall had been set at liberty; that favours had been extended to various political prisoners; and that Collins was again blowing the dying embers of Birmingham Chartism to a blaze. (Laughter.) He thought that the display of feeling they had that day made would at all events convince the writer of this article that it did not require much blowing on his part to blow Chartism in Manchester to a blaze. (Cheers.)

"He had long been convinced that no converts were ever made to an opinion by fine, or imprisonment, or banishment; and if he had wanted any additional argument that this was the case, it would have been afforded by the magnificent display that day made in the streets of Manchester in favour of men who had been imprisoned for their cause. (Great cheering.) He felt sure that the plans which had been adopted by the enemies of labour were the very best calculated to spread the Charter far and wide, and to impress upon the breast of every man the necessity of making any sacrifice, however great, for the attainment of that most desirable object; he felt certain that the advocacy of Chartist principles in courts of justice, and the refusal of Parliament to inquire into the treatment of Chartist prisoners, must impress on the mind of every thinking man the importance of the principles they advocated.

"The very excellent remarks which had fallen from Dr McDouall had given him a great deal of pleasure; and he would avail himself of that opportunity of conveying to the worthy doctor, in the name and on the behalf of the committee and the great body of the Chartists in Birmingham, the expression of their congratulations on his leaving his dungeon, and of their sympathies with his sufferings while immured in it. He would also assure him that on Monday the men of Birmingham had redeemed their pledge at a great meeting on foreign politics at Holloway Head - that pledge which had not only been made there, but at Peep Green, Kersal Moor, and all the large meetings throughout the country - the pledge that they would never agitate for any other subject - never turn to the right hand or to the left never cease their exertions till the principles of the Charter became the law of the land. (Great cheering.)

"His friend, McDouall, had said that since he came out of prison (where he had been himself), the only argument he had heard against the Charter was that the working classes were not prepared to exercise the Suffrage. Now, he thought this was a mistake on the Doctor's part. He thought this was no argument at all, but merely assertion. He thought proof was necessary to constitute an argument. To be sure he did not profess to be very learned in the matters, because, from the time he was very young, he had worked for his bread; but he never thought assertions were arguments. Now, he believed that the working men as a class (for, of course, there were exceptions) were - he was going to say as fit, but he would say more fit, than any other to exercise the franchise. (Cheers.) And when their opponents said the Chartists wished to give every dishonest man a vote, he would reply that the statement was a foul calumny. The Charter made an express provision to the contrary, while, at present, if a man possessed the requisite amount of property, he voted, whether honest or dishonest; so that even if it were true the Charter made no provision to the contrary, the Radicals might reply that they did not see why a poor rogue should not have a vote as well as a rich one. (Cheers, and laughter.)

"If he were disposed to look on the assertion as an argument, he would say, by giving them a vote you would raise them in their own opinion. A man who was treated badly became reckless of consequences; but if, on the contrary, he knew he had the confidence of his neighbours he would endeavour to show that confidence was not misplaced. It might be illustrated by 10,000 instances from every day life. When a man stepped out in the morning with his shoes well blacked, he took care to pick his way through the streets lest he should soil them; but when they had become thoroughly dirty, he came splashing through every gutter home. (Laughter.) It was the same thing in morality. If a man were treated as not fit to be depended upon he would act accordingly. Neither was the way to raise a man to imprison him for advocating the rights of liberty; and he was sure the treatment of the advocates of the people's cause would only increase the indignation of the people, and deepen more and more the impression of the justice of their principles and the injustice of their oppressors. (Loud cheers.)

"Look at their situation. A population ill-fed and ill-clothed, toiling incessantly from morning to night. He held in his hand a copy of correspondence which took place respecting himself and his friend Lovett - (cheers) - and it contained the testimony of Sir Eardley Wilmot, a magistrate and Member of Parliament, that ninety-nine out of a hundred labourers were worse fed and clothed than felons in the prison. (Cries of 'Shame, shame') They had experience of its truth. They heard of times of adversity and times of prosperity. Why, what was the difference to the working man? If times were a little better they only served him to get out of debt, and to take away his things from the pawnbrokers - (hear, hear) - and then came the panic again, and he got into debt once more, and his goods were again pledged. The talk of prosperity and adversity was all stuff and nonsense - it was all adversity to the working man. ('Well done, Collins,' and cheers.)

"With the people breaking stones upon the roads, and their wives and little ones starving at home, was it to be wondered at that some should have talked of physical force. He could speak freely on this head, as he had never advocated physical force - he had been called an old Brummagem ginger bread woman for not doing so - (laughter) - yet he did not wonder that some men, goaded to madness should have resorted to threats of violence, especially when he considered the sort of education they had received. (Hear, hear.) Some had none at all; and others were taught words instead of ideas. They had been taught to look up with veneration to generals who had sacked towns, depopulated villages, and made thousands of widows and orphans, and consider them the greatest men the world ever saw; and was it to be wondered at that they acted as they had done. He trusted they would soon be able to wield the far superior power of moral force, which would enable them to establish themselves in that position which they ought to occupy. Much as had been said on the subject of physical force, it had all along been the great argument of their enemies, who had turned this country into one great arsenal to put down the demand for the Charter. (Cheers.) They might continue to spread their blue-coated gentry throughout the land, but they would never be able to change the eternal truth contained in their principles - they might go on extending their military force as much as they pleased, but they would never reconcile the people of the country to poverty, misery, and degradation. (Great cheering.) God had decreed that they should eat their bread by the sweat of their brow; but man had ordained that their brows should sweat, but that the bread should be eaten by others. This they were not content to do. (Cheers.)

"But he would now conclude. They were tired, and he was tired. ('No, no.') He was tired, at least, and he felt it was not in good taste to keep them there any longer after the fatigues of the procession, especially as he should again have an opportunity of addressing them on Monday. He hoped, indeed, that he should meet them often - for it was only by the interchange of converse between man and man that they could hope to improve their condition. It was not by groaning, or shouting, or hissing, that they would gain their object, but by meeting and instructing each other.

"Again thanking them for the glorious display which they had made that day - and again congratulating them on the presence of McDouall once more amongst them, he begged to express, in Mr Lovett's name, his regret at not being able to visit them. Nothing but weakness of frame prevented him from coming; his heart had never quailed - his spirit had never shrunk from the cause - (cheers) - though his body had been bent down, and, he was sorry to say, his constitution was so weakened and impaired, that it was doubtful whether he would ever be the man again he formerly was. (Loud cries of 'Shame, shame! The bloody Whigs!) Still the heart and the spirit of the noble patriot never failed him; and he (Mr Collins) was the bearer of the expression of his attachment to the cause of liberty, and of his determination still to advocate it with all the strength that tyrants had left him, and with all the ability that God had given him.

"Mr Collins then sat down amidst prolonged cheering."

"He had long been convinced that no converts were ever made to an opinion by fine, or imprisonment, or banishment; and if he had wanted any additional argument that this was the case, it would have been afforded by the magnificent display that day made in the streets of Manchester in favour of men who had been imprisoned for their cause. (Great cheering.) He felt sure that the plans which had been adopted by the enemies of labour were the very best calculated to spread the Charter far and wide, and to impress upon the breast of every man the necessity of making any sacrifice, however great, for the attainment of that most desirable object; he felt certain that the advocacy of Chartist principles in courts of justice, and the refusal of Parliament to inquire into the treatment of Chartist prisoners, must impress on the mind of every thinking man the importance of the principles they advocated.

"The very excellent remarks which had fallen from Dr McDouall had given him a great deal of pleasure; and he would avail himself of that opportunity of conveying to the worthy doctor, in the name and on the behalf of the committee and the great body of the Chartists in Birmingham, the expression of their congratulations on his leaving his dungeon, and of their sympathies with his sufferings while immured in it. He would also assure him that on Monday the men of Birmingham had redeemed their pledge at a great meeting on foreign politics at Holloway Head - that pledge which had not only been made there, but at Peep Green, Kersal Moor, and all the large meetings throughout the country - the pledge that they would never agitate for any other subject - never turn to the right hand or to the left never cease their exertions till the principles of the Charter became the law of the land. (Great cheering.)

"His friend, McDouall, had said that since he came out of prison (where he had been himself), the only argument he had heard against the Charter was that the working classes were not prepared to exercise the Suffrage. Now, he thought this was a mistake on the Doctor's part. He thought this was no argument at all, but merely assertion. He thought proof was necessary to constitute an argument. To be sure he did not profess to be very learned in the matters, because, from the time he was very young, he had worked for his bread; but he never thought assertions were arguments. Now, he believed that the working men as a class (for, of course, there were exceptions) were - he was going to say as fit, but he would say more fit, than any other to exercise the franchise. (Cheers.) And when their opponents said the Chartists wished to give every dishonest man a vote, he would reply that the statement was a foul calumny. The Charter made an express provision to the contrary, while, at present, if a man possessed the requisite amount of property, he voted, whether honest or dishonest; so that even if it were true the Charter made no provision to the contrary, the Radicals might reply that they did not see why a poor rogue should not have a vote as well as a rich one. (Cheers, and laughter.)

"If he were disposed to look on the assertion as an argument, he would say, by giving them a vote you would raise them in their own opinion. A man who was treated badly became reckless of consequences; but if, on the contrary, he knew he had the confidence of his neighbours he would endeavour to show that confidence was not misplaced. It might be illustrated by 10,000 instances from every day life. When a man stepped out in the morning with his shoes well blacked, he took care to pick his way through the streets lest he should soil them; but when they had become thoroughly dirty, he came splashing through every gutter home. (Laughter.) It was the same thing in morality. If a man were treated as not fit to be depended upon he would act accordingly. Neither was the way to raise a man to imprison him for advocating the rights of liberty; and he was sure the treatment of the advocates of the people's cause would only increase the indignation of the people, and deepen more and more the impression of the justice of their principles and the injustice of their oppressors. (Loud cheers.)

"Look at their situation. A population ill-fed and ill-clothed, toiling incessantly from morning to night. He held in his hand a copy of correspondence which took place respecting himself and his friend Lovett - (cheers) - and it contained the testimony of Sir Eardley Wilmot, a magistrate and Member of Parliament, that ninety-nine out of a hundred labourers were worse fed and clothed than felons in the prison. (Cries of 'Shame, shame') They had experience of its truth. They heard of times of adversity and times of prosperity. Why, what was the difference to the working man? If times were a little better they only served him to get out of debt, and to take away his things from the pawnbrokers - (hear, hear) - and then came the panic again, and he got into debt once more, and his goods were again pledged. The talk of prosperity and adversity was all stuff and nonsense - it was all adversity to the working man. ('Well done, Collins,' and cheers.)

"With the people breaking stones upon the roads, and their wives and little ones starving at home, was it to be wondered at that some should have talked of physical force. He could speak freely on this head, as he had never advocated physical force - he had been called an old Brummagem ginger bread woman for not doing so - (laughter) - yet he did not wonder that some men, goaded to madness should have resorted to threats of violence, especially when he considered the sort of education they had received. (Hear, hear.) Some had none at all; and others were taught words instead of ideas. They had been taught to look up with veneration to generals who had sacked towns, depopulated villages, and made thousands of widows and orphans, and consider them the greatest men the world ever saw; and was it to be wondered at that they acted as they had done. He trusted they would soon be able to wield the far superior power of moral force, which would enable them to establish themselves in that position which they ought to occupy. Much as had been said on the subject of physical force, it had all along been the great argument of their enemies, who had turned this country into one great arsenal to put down the demand for the Charter. (Cheers.) They might continue to spread their blue-coated gentry throughout the land, but they would never be able to change the eternal truth contained in their principles - they might go on extending their military force as much as they pleased, but they would never reconcile the people of the country to poverty, misery, and degradation. (Great cheering.) God had decreed that they should eat their bread by the sweat of their brow; but man had ordained that their brows should sweat, but that the bread should be eaten by others. This they were not content to do. (Cheers.)

"But he would now conclude. They were tired, and he was tired. ('No, no.') He was tired, at least, and he felt it was not in good taste to keep them there any longer after the fatigues of the procession, especially as he should again have an opportunity of addressing them on Monday. He hoped, indeed, that he should meet them often - for it was only by the interchange of converse between man and man that they could hope to improve their condition. It was not by groaning, or shouting, or hissing, that they would gain their object, but by meeting and instructing each other.

"Again thanking them for the glorious display which they had made that day - and again congratulating them on the presence of McDouall once more amongst them, he begged to express, in Mr Lovett's name, his regret at not being able to visit them. Nothing but weakness of frame prevented him from coming; his heart had never quailed - his spirit had never shrunk from the cause - (cheers) - though his body had been bent down, and, he was sorry to say, his constitution was so weakened and impaired, that it was doubtful whether he would ever be the man again he formerly was. (Loud cries of 'Shame, shame! The bloody Whigs!) Still the heart and the spirit of the noble patriot never failed him; and he (Mr Collins) was the bearer of the expression of his attachment to the cause of liberty, and of his determination still to advocate it with all the strength that tyrants had left him, and with all the ability that God had given him.

"Mr Collins then sat down amidst prolonged cheering."

4. THE COMPLETE SUFFRAGE UNION - JOHN COLLINS SPEAKS

Beginning late 1841, the Complete Suffrage Union was founded by Joseph Sturge a Quaker corn merchant and free trader in Birmingham. He wanted to unite the middle and working classes in a peaceful campaign for political reform, and a conference was arranged in Birmingham for April 5th 1942. The conference comprised over eighty delegates and attracted the support of various middle and working class factions including the famed radical and statesmen John Bright. There were London artisans William Lovett and Henry Vincent, and Christian Chartists represented by John Collins and Arthur O'Neill.

Sturge and his middle class supporters wanted John Collins involved because he was a steady, moderate working class man who was well respected in Birmingham and known to favour unity and peaceful means to gain reform. In spite of this, Collins' speech on the first day of the CSU conference made no bones about where he stood.

Sturge and his middle class supporters wanted John Collins involved because he was a steady, moderate working class man who was well respected in Birmingham and known to favour unity and peaceful means to gain reform. In spite of this, Collins' speech on the first day of the CSU conference made no bones about where he stood.

"Mr John Collins then said - Mr Chairman and gentlemen, the subject now adverted to by John Dunlop, Esq., is one of great importance, and probably it is well that it is brought forward at this early stage of our proceedings rather than at an after period.

"It is not wise, if there be any sore existing, to attempt to skin over the surface without probing the wound to the bottom. If I understand the object of this conference, it is to endeavour, if possible, to unite the middle and working classes; and, sir, this can only be done by declaring for a full measure of justice - half and half measures will not accomplish the object - and I think that we should unequivocally declare that we have no intention of adopting any other than Christian and peaceable means for carrying out our objects; without this no association can be formed of any very extensive kind.

"And now, sir, you will allow me to observe, that I think too much has been said against the class of which I have the honour to be one (I mean the working class) by those from whom better things might have been expected. I am not aware that any man has ever charged me with being violent myself, or with recommending violence either to the persons or property of others, and therefore I can speak a little more boldly upon this subject than many others. And, sir, while I am prepared to admit that many of my brethren have said and done things exceedingly foolish, yet let us for a moment consider the nature of their education and circumstances, and if we do not find many reasons to judge them less harshly I am much mistaken.

"Why, sir, in their infantile play, toys in the shape of swords, and guns, and pistols, and drums, were put into their hands, and their parents laughed at their imitations of contests between the French and English; and then, as they grew older, pictures of military and naval heroes were put into their hands, and they were led to admire their exploits, and taught to regard them as the most important personages that ever lived. Then, sir, as they take their walks through their respective towns and cities, what do they see? Why, they have their Nelson streets, their Wellington hotels, and Waterloo squares and bridges, and thus a love of martial glory is infused into their minds; nor did it stop here - no, sir, for the songs written for their social hours, as they advanced more into life, were written to produce or strengthen these feelings. Hence their burdens were, “March to the battle field,” “On to the charge, ye brave,” “O’er Nelsons tomb Britannia mourns.” And more than all this, when they entered the place that should be the sanctuary of the Most High, and the temple of peace, it was desecrated by prayers to God for success of arms, and thanksgiving for victory that consigned thousands or tens of thousands to untimely graves, and made thousands of widows, and tens of thousands of children fatherless; and when you add to this the effect produced by the mockery of consecrating a banner to be presented by an aristocratical lady to a regiment, under which they are to march to embrue their hands in blood, to ransack towns, and desolate whole countries - when, sir, I say, all these things are considered, and add to them the mental suffering endured from seeing the wives of their bosom, and the children of their loins, pining for want, not of the comforts, but even the necessaries of life, shall we not find many reasons why we should refrain from taunting the whole of the working class for things that are past; and indeed, may we not rather wonder that more errors were not committed of a similar character with those the working men themselves so much deplore?

"Again, sir, it has been said they willingly follow violent and designing leaders. Why is this? Is it not because gentlemen of a more peaceable and intellectual character have sat supinely by and regarded not their miseries, nor attempted to obtain justice for the masses, so long as they could ease themselves by shifting the burdens upon the shoulders of their workmen, by reducing wages and various other means.

"I speak this not in anger, but in sorrow; and I now hope that the object of our venerated chairman will be accomplished, that we shall now cease to taunt each other; and, sincerely forgiving the mutual errors of the past, we shall once more cordially shake hands and go forth together in one great and glorious movement.

"I feel it my duty, however, in conclusion, again to tell you, that in order to secure the hearty co-operation of the working classes, you must avoid half measures - you must go for a full measure of justice, and then I have no fear of the result."

"It is not wise, if there be any sore existing, to attempt to skin over the surface without probing the wound to the bottom. If I understand the object of this conference, it is to endeavour, if possible, to unite the middle and working classes; and, sir, this can only be done by declaring for a full measure of justice - half and half measures will not accomplish the object - and I think that we should unequivocally declare that we have no intention of adopting any other than Christian and peaceable means for carrying out our objects; without this no association can be formed of any very extensive kind.

"And now, sir, you will allow me to observe, that I think too much has been said against the class of which I have the honour to be one (I mean the working class) by those from whom better things might have been expected. I am not aware that any man has ever charged me with being violent myself, or with recommending violence either to the persons or property of others, and therefore I can speak a little more boldly upon this subject than many others. And, sir, while I am prepared to admit that many of my brethren have said and done things exceedingly foolish, yet let us for a moment consider the nature of their education and circumstances, and if we do not find many reasons to judge them less harshly I am much mistaken.

"Why, sir, in their infantile play, toys in the shape of swords, and guns, and pistols, and drums, were put into their hands, and their parents laughed at their imitations of contests between the French and English; and then, as they grew older, pictures of military and naval heroes were put into their hands, and they were led to admire their exploits, and taught to regard them as the most important personages that ever lived. Then, sir, as they take their walks through their respective towns and cities, what do they see? Why, they have their Nelson streets, their Wellington hotels, and Waterloo squares and bridges, and thus a love of martial glory is infused into their minds; nor did it stop here - no, sir, for the songs written for their social hours, as they advanced more into life, were written to produce or strengthen these feelings. Hence their burdens were, “March to the battle field,” “On to the charge, ye brave,” “O’er Nelsons tomb Britannia mourns.” And more than all this, when they entered the place that should be the sanctuary of the Most High, and the temple of peace, it was desecrated by prayers to God for success of arms, and thanksgiving for victory that consigned thousands or tens of thousands to untimely graves, and made thousands of widows, and tens of thousands of children fatherless; and when you add to this the effect produced by the mockery of consecrating a banner to be presented by an aristocratical lady to a regiment, under which they are to march to embrue their hands in blood, to ransack towns, and desolate whole countries - when, sir, I say, all these things are considered, and add to them the mental suffering endured from seeing the wives of their bosom, and the children of their loins, pining for want, not of the comforts, but even the necessaries of life, shall we not find many reasons why we should refrain from taunting the whole of the working class for things that are past; and indeed, may we not rather wonder that more errors were not committed of a similar character with those the working men themselves so much deplore?

"Again, sir, it has been said they willingly follow violent and designing leaders. Why is this? Is it not because gentlemen of a more peaceable and intellectual character have sat supinely by and regarded not their miseries, nor attempted to obtain justice for the masses, so long as they could ease themselves by shifting the burdens upon the shoulders of their workmen, by reducing wages and various other means.

"I speak this not in anger, but in sorrow; and I now hope that the object of our venerated chairman will be accomplished, that we shall now cease to taunt each other; and, sincerely forgiving the mutual errors of the past, we shall once more cordially shake hands and go forth together in one great and glorious movement.

"I feel it my duty, however, in conclusion, again to tell you, that in order to secure the hearty co-operation of the working classes, you must avoid half measures - you must go for a full measure of justice, and then I have no fear of the result."