THE CHARTIST MOVEMENT

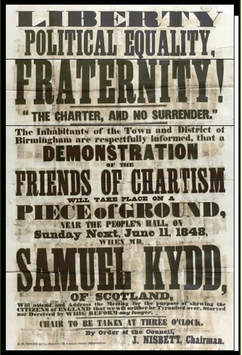

The Chartist Movement, was a nationwide campaign (1838-1848) that fought for the rights of working class men, especially their right to vote, in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland. Chartism itself morphed out of the people's social and political dissatisfaction brought to a head through mass meetings and demonstrations led by three major entities: the Birmingham Political Union, the London Working Men's Association, and the northern unions that eventually formed the Great Northern Union.

|

It came about at a time of acute poverty and distress, and it was because of this that John Collins came out in the public cause and became a leader in the Chartist Movement. He said on more than one occasion he saw people dying of want. When Collins canvassed a whole street in Birmingham (England) he found but one family that was living in relative comfort in January 1838. Most people were unemployed and in desperate straits.

|

Predominantly made up of working class radicals, agitators and political unions, the Chartist Movement promoted the famed "six points" including universal male suffrage, voting by secret ballot, and other electoral reforms (see below) as laid out in the National Petition and the The People's Charter.

LEADERS OF THE CHARTIST MOVEMENT

|

"The Organization (Chartist Movement) was the product of a merger between the London Working Men's Association, led by William Lovett and Henry Vincent; the Birmingham Political Union, including Thomas Attwood and John Collins; and the (northern) political unions organized by Feargus O'Connor."

W Slossom, Decline of the Chartist Movement |

The Birmingham Political Union (BPU)

Although Thomas Attwood helped revive the defunct Birmingham Political Union (BPU) in 1837, he did not play a major role in the ensuing Chartist Movement. Douglas, Salt and John Collins - all council members of the BPU - led that charge from Birmingham. Prior to that, and until becoming elected a council member of the BPU in 1837, John Collins had lived life as a working man in relative obscurity. Having become radicalized by the terrible economical effects on his working class neighbours, Collin rose to become one of the most well-known and effective of the working class leaders in the early years of the Chartist Movement. For John Collins' contribution to the Chartist Movement please go to Chartist Leader and the Bull Ring Riots, both on this website.

Mainly an absentee figurehead of the BPU, Attwood did not take part in the actual agitation of the Chartist Movement and was barely involved in Chartism's progress - except for assuming the leading role at certain major demonstrations. When John Collins' campaign for the suffrage in Scotland proved such a success, and the BPU council made plans for the Great Demonstrations at Glasgow and Birmingham, Attwood stepped in and took center stage. In the words of Carlos Flick [The Birmingham Political Union 1830-1839]: "This desire for the chief position later led him [Attwood] to claim personal credit, falsely, for almost the entire plan of agitation."

The Birmingham Political Union devised the first Chartist Petition - officially known as the National Petition. This document signed by over 1.25 million people was presented to Parliament in 1839 and demanded changes to the unfair electoral system which gave only the moneyed and propertied upper and middle classes the right to vote. The poor, working class people were unable to vote.

Mainly an absentee figurehead of the BPU, Attwood did not take part in the actual agitation of the Chartist Movement and was barely involved in Chartism's progress - except for assuming the leading role at certain major demonstrations. When John Collins' campaign for the suffrage in Scotland proved such a success, and the BPU council made plans for the Great Demonstrations at Glasgow and Birmingham, Attwood stepped in and took center stage. In the words of Carlos Flick [The Birmingham Political Union 1830-1839]: "This desire for the chief position later led him [Attwood] to claim personal credit, falsely, for almost the entire plan of agitation."

The Birmingham Political Union devised the first Chartist Petition - officially known as the National Petition. This document signed by over 1.25 million people was presented to Parliament in 1839 and demanded changes to the unfair electoral system which gave only the moneyed and propertied upper and middle classes the right to vote. The poor, working class people were unable to vote.

|

The National Petition called for the following points of reform (the same as The People's Charter):

- The right to vote for every man (universal male suffrage) over the age of 21 years - No property qualifications required in order to stand for Parliament - Annual elections for Parliament - Equal-sized electoral districts - Members of Parliament to be paid - The right to vote by secret ballot For the complete text of the 1839 National Petition on this website, click on this link: National Petition |

The London Working Men's Association (LWMA)

|

The London Working Men's Association (LWMA) was founded in June 1836 by some of the leading working class radicals of the day, including William Lovett, a cabinet maker, and Francis Place, a tailor.

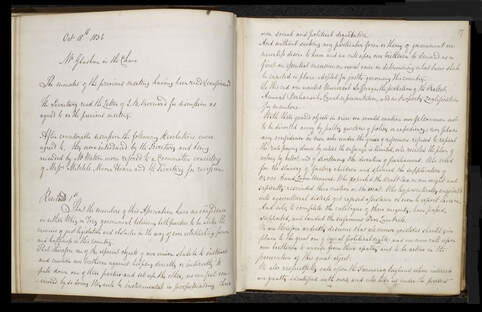

In October 1836 the LWMA approved a Resolution calling for “an equal voice in determining what laws shall be enacted or plans adopted for justly governing this country.” To this end they listed universal suffrage and four other points of electoral reform (see the LWMA Minutes dated 16 Oct 1836). Those original five points plus one more would eventually form the basis of the famed People’s Charter published in May 1838. The People's Charter gave its name to the Chartist Movement. |

The LWMA was much smaller than the Birmingham Political Union (BPU) and Great Northern Union (GNU), the two organizations that dominated the Chartist Movement. Unlike them, the LWMA was made up of skilled craftsmen as opposed to working class factory hands. The LWMA, led by William Lovett, stood for education and reform through peaceful means, and was more aligned with the BPU middle class leaders, and especially its moderate, non-violent working class leader John Collins. The LWMA was also willing to try to work with the middle classes to gain reform, and this caused much dissention and rivalry between the quiet unassuming William Lovett and the swaggering orator Feargus O’Connor, who was the leader of the GNU, with a very different philosophy.

The Great Northern Union (GNU)

The leaders of the Chartist Movement tended to fall into two groups: "moral force" and "physical force" men depending upon their attitudes toward violent protest. For instance, John Collins of Birmingham Political Union and William Lovett of the London Working Men's Association belonged to the former group, preferring moderate, persuasive speech-making together with rallies and petitions in order to gain reform. Feargus O'Connor, the leader of the Great Northern Union, fell in the latter group coming across as a demagogue and a bully. His use of threats and aggressive rhetoric appealed to the working men of the north who were especially affected by poverty and distress. For more on moral and physical force Chartists please click here.

In 1837, Feargus O'Connor founded the newspaper the Northern Star & Leeds General, which became the mouthpiece for O'Connor and helped promote his ascendancy in the Chartist Movement. The following year O'Connor helped establish the Great Northern Union which, together with the BPU and the LWMA, formed the Chartist Movement's unofficial triumvirate partnership. It was an alliance that did not last very long, and ended with O'Connor taking over as the supreme leader of the Chartist Movement.

In 1837, Feargus O'Connor founded the newspaper the Northern Star & Leeds General, which became the mouthpiece for O'Connor and helped promote his ascendancy in the Chartist Movement. The following year O'Connor helped establish the Great Northern Union which, together with the BPU and the LWMA, formed the Chartist Movement's unofficial triumvirate partnership. It was an alliance that did not last very long, and ended with O'Connor taking over as the supreme leader of the Chartist Movement.

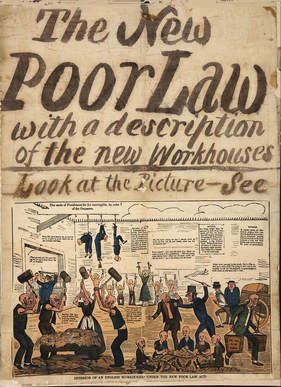

CAUSES OF THE CHARTIST MOVEMENTExclusion

Chartism has been called the first mass working class movement in the world, finding a foothold in the disappointing outcome of the 1832 Reform Act that extended the vote to the middle class (via property qualification) and effectively excluded the lower class since they did not own any property. However, there was more to this scenario than meets the eye. Injustice It is true that the failure of the 1832 Reform Act left a great sense of political injustice among the 'thinking' working men and artisan classes, but when combined with a poor economy, deplorable living and working conditions, and the draconian Poor Law the lower, unskilled working class understood all too clearly the reality of their exclusion from the voting system. Poverty Some might have thought suffrage would miraculously ease poverty and distress, nevertheless, men like John Collins and the other leaders of the Chartist Movement, had the sense to know that by being eligible to vote they could install Members of Parliament who truly represented working men and their interests, and who would work to repeal the Corn Law and other laws that favoured the rich at the expense of the poor. |

The Corn Laws imposed a tariff on imported wheat, protecting British farmers from foreign competition, but making the cost of bread artificially high. Meanwhile, the mass of people had no control over government taxes and spending, they had no say on the price of bread, and they had no share in the profits of industry.

Chartism was also a class struggle: working class people suffered when times were good (low wages and harsh factory conditions), and they suffered still more when times were bad (unemployment and the brutal Poor Law) , and it fueled their resentment for the privileged, ruling class. All it needed were the likes of men such as John Collins of the Birmingham Political Union, William Lovett of the London Working Men's Association, and Feargus O'Connor heading the Northern Unions - with their vision for a better country and a better future - to galvanize the deprived and disillusioned masses into action and join the cause for democratic reform. Thus the scene was set for the Chartist Era.

Chartism was also a class struggle: working class people suffered when times were good (low wages and harsh factory conditions), and they suffered still more when times were bad (unemployment and the brutal Poor Law) , and it fueled their resentment for the privileged, ruling class. All it needed were the likes of men such as John Collins of the Birmingham Political Union, William Lovett of the London Working Men's Association, and Feargus O'Connor heading the Northern Unions - with their vision for a better country and a better future - to galvanize the deprived and disillusioned masses into action and join the cause for democratic reform. Thus the scene was set for the Chartist Era.

|

A Mr Richardson of Manchester, speaking on behalf of the starving hand loom weavers of Lancashire, put it this way:

"I am here this day to support the National Petition and the People's Charter because it demands Universal Suffrage, because it gives them [the people] a vote in the choice of representatives. They are justified in demanding it. Is it too much for those who produce all the food, all the clothing, all the luxuries of life, who fight all the battles of the country, to ask for a voice in the choice of representatives." 17 September 1838 |

THE PEOPLE'S CHARTER & THE SIX POINTS OF REFORM

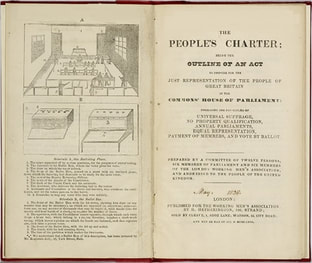

The People's Charter (later known simply as "The Charter") was a document drawn up by the London Working Men's Association (founded in 1836) together with several sympathetic Members of Parliament. It took the form of a proposed Act of Parliament that if passed into law would have made the political system more democratic.

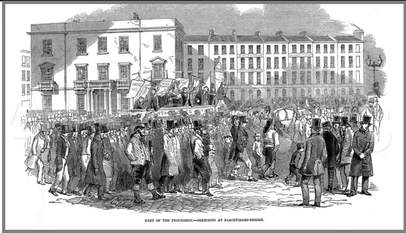

The People's Charter was publicly launched on 21st May 1838 at a huge demonstration on Glasgow Green, Scotland - and that demonstration came about thanks in large part to the enormous campaign efforts of John Collins, a leading spokesman for the Birmingham Political Union, in which he fired up the spirit and support of the men of Scotland.

Although the People's Charter became the rallying cry for the Chartist Movement, "The Charter" itself was never introduced to Parliament since the government of the day refused to consider the people's claims for parliamentary reform.

The People's Charter was publicly launched on 21st May 1838 at a huge demonstration on Glasgow Green, Scotland - and that demonstration came about thanks in large part to the enormous campaign efforts of John Collins, a leading spokesman for the Birmingham Political Union, in which he fired up the spirit and support of the men of Scotland.

Although the People's Charter became the rallying cry for the Chartist Movement, "The Charter" itself was never introduced to Parliament since the government of the day refused to consider the people's claims for parliamentary reform.

|

The Six Points of The People's Charter

The People's Charter basically consisted six main principles of reform, and its title leant its name to the Chartist Movement:

- Universal Suffrage for men over the age of 21 years

- No property qualifications to stand for Parliament - Annual elections for Parliament - Equal-sized electoral districts - Members of Parliament to be paid - Voting by secret ballot |

What is a Chartist?

A pro-Chartist pamphlet entitled "The Question 'What is a Chartist?' Answered" was published by the Finsbury Tract Society in 1839 for 1s. 6d per hundred, or five for a penny. It offered answers to popular Chartism questions posed by a "Mr Doubtful."

A pro-Chartist pamphlet entitled "The Question 'What is a Chartist?' Answered" was published by the Finsbury Tract Society in 1839 for 1s. 6d per hundred, or five for a penny. It offered answers to popular Chartism questions posed by a "Mr Doubtful."

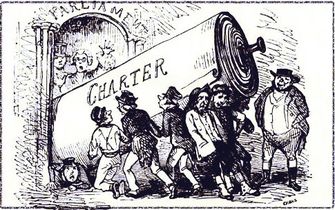

PETITIONING GOVERNMENT WITH THE PEOPLE'S GRIEVANCES

Since the man on the street had no "voice" or representation to speak for them at government level, petitioning was an accepted form of contacting Parliament for the working class. During the course of the Chartist Movement the Chartists submitted three National Petitions to Parliament - all of which were rejected, and the last of which was something of a fiasco since less than half the five million signatures proved genuine. The National Petitions with their millions of signatures were a way of formally bringing the people's grievances and the famed "People's Charter" to the attention of Parliament.

On 1st May 1838 a committee of the Birmingham Political Union (BPU) sat down to draw up the first National Petition that addressed the unfair political system. Previously, the BPU had stood for five points or principals of reform, including household suffrage (rather than universal suffrage), triennial parliaments (rather than annual parliaments), paid MPs, no property qualifications, and the ballot. It excluded equal size electoral districts. However, by the middle of May the Union had publicly approved the same six points as the People's Charter, beating the actual publication of the People's Charter by several days. John Collins was apparently the driving force behind the change from triennial to annual parliaments (Birmingham Political Union 1830-1839, Flick, p 136), and was already advocating it during his tour of Scotland (Fife Herald 19 April 1838).

|

The idea for a huge nationwide Petition had been presented in February 1838, by BPU council member, Mr T C Salt, when he talked about a possible campaign in Scotland and the North for collecting signatures in support of a National Petition.

Subsequently, John Collins said he hoped the council would soon be able to send a "pioneer" to pave the way for such a campaign [Birmingham Journal, 3 March 1838] and by April he had taken on that task travelling hundreds of miles and speaking before thousands of people in Scotland and the North of England. (For more on Collins' campaign in Scotland, please see Chartist Leader on this website.) Yet a further council member of the BPU, Mr P H Muntz, put forward the idea for the large towns in Britain to elect representatives (also known as Delegates) to attend a General Convention with authority to manage the Movement and the presentation of the National Petition to Parliament. |

Following many mass meetings and demonstrations in support of the National Petition, the General Convention of the Industrious Classes met in London from February to May 1839. The Convention formed a Petition Committee that included John Collins. Thousands of petition signatures were sent to him from all over the country (Lovett Papers, Birmingham Archives & Heritage). The Petition was to be "conveyed to Parliament by the Convention as a first act, to demonstrate the determination of the people to have democracy, and then immediately after, the People's Charter would be introduced into the House of Commons by reformer MPs as a means of forcing the legislators to debate and vote on the democratic program." Click here to read the text of the National Petition.

THREE CHARTIST PETITIONS

First National Petition (Rejected by 189 votes):

On May 5th 1839 Thomas Attwood, Member of Parliament for Birmingham, reported John Collins has handed him the National Petition as promised, and Collins reported from the Petition Committee that he had now redeemed his pledge that the Petition was ready (Lovett Papers, Library of Birmingham Archives). Accordingly, the first National Petition was introduced to the House of Commons in mid-June 1839 by Thomas Attwood MP. A month later he made a motion (seconded by John Fielden MP) that the House resolve itself into a Committee of the whole House to consider the demands in the National Petition.

It had over 1.25 million signatures from 214 towns and villages, and over 500 meetings. John Collins claimed it had 24,000 women's signatures (Vallance, A Radical History of Britain). The National Petition was "unequaled in the history of parliamentary history." Nevertheless, it was rejected out of hand by Parliament by 235 votes to 46.

One of the 'Noes' was the Member of Parliament for Glasgow - who, needless to say, did not represent the vast working class population of Glasgow who had signed the National Petition! Another 'No' was Benjamin D'Israeli. For a list of those MPs for and against the National Petition please click here. Following the failure of this Petition, Thomas Attwood resigned from politics.

On May 5th 1839 Thomas Attwood, Member of Parliament for Birmingham, reported John Collins has handed him the National Petition as promised, and Collins reported from the Petition Committee that he had now redeemed his pledge that the Petition was ready (Lovett Papers, Library of Birmingham Archives). Accordingly, the first National Petition was introduced to the House of Commons in mid-June 1839 by Thomas Attwood MP. A month later he made a motion (seconded by John Fielden MP) that the House resolve itself into a Committee of the whole House to consider the demands in the National Petition.

It had over 1.25 million signatures from 214 towns and villages, and over 500 meetings. John Collins claimed it had 24,000 women's signatures (Vallance, A Radical History of Britain). The National Petition was "unequaled in the history of parliamentary history." Nevertheless, it was rejected out of hand by Parliament by 235 votes to 46.

One of the 'Noes' was the Member of Parliament for Glasgow - who, needless to say, did not represent the vast working class population of Glasgow who had signed the National Petition! Another 'No' was Benjamin D'Israeli. For a list of those MPs for and against the National Petition please click here. Following the failure of this Petition, Thomas Attwood resigned from politics.

|

Third National Petition (1,975,496 genuine signatures):

April 1848, the third National Petition was said to have over 5 million signatures. However, the government claimed 3 million were fake, including signatures of Queen Victoria, the Duke of Wellington, April First, etc, with numerous sheets in the same handwriting! Presented by Feargus O'Connor MP for Nottingham, the petition was not only rejected by Parliament it was ridiculed and discredited.

April 1848, the third National Petition was said to have over 5 million signatures. However, the government claimed 3 million were fake, including signatures of Queen Victoria, the Duke of Wellington, April First, etc, with numerous sheets in the same handwriting! Presented by Feargus O'Connor MP for Nottingham, the petition was not only rejected by Parliament it was ridiculed and discredited.

|

CHARTISM'S DEMISE

|

The failure of the last great Chartist Petition virtually rang the death knell for the Chartist Movement, and in spite of its then current leaders' attempts to keep it going the Movement had greatly lost its legs.

Robert Gammage and post-Chartism authors blamed the militant leadership (in particular, Feargus O'Connor) for the decline and fall of the Chartist Movement. Feargus O'Connor was a great leader in that he charmed and fired up the mass of working class people on a grand and national scale. However, we should not forget that he had a lot of help from the London Men's Working Association and the Birmingham Political Union who helped kick-start the Chartist Movement. |

Nor should we forget it was William Lovett who wrote the People's Charter, and it was John Collins who roused the men of Scotland to join the English reform movement which in turn helped provide the impetus for the Chartist Movement on a national scale.

|

Moreover, Feargus O'Connor was a notorious demogogue, not known for diplomacy or cooperation. He rubbed many people the wrong way through his forceful language and tone, not to mention personal attacks on those reformers (such as John Collins and William Lovett) who held differing strategies or points of view.

O'Connor united the masses under one banner - the physical force banner - but that left no room for advocates of peaceful means and class unity in order to gain reform. In doing so O'Connor alienated and frightened off potential allies and moderate Chartists who would have been great service to the Movement. |

The councilmen of the Birmingham Political Union once accused O'Connor of promoting himself unlike John Collins who promoted the Movement. To some degree that was true. The working class fell in love with O'Connor's loud, passionate no-holds-barred rhetoric because they were frustrated with an unfair system and he told them what they wanted to hear even though his threats of violence and insurrection were doomed to fail.

Chartism was tainted by physical force advocates from the get-go, as was seen in the comments of Members of Parliament when the first National Petition was presented to the government. As one Member put it: "I am opposed altogether to every exertion of physical force in attaining these objects, more especially when I observe that those who stimulate the people to violence are most careful to remain at a distance when the army comes down upon the victims of their advice."

In the end Chartism boiled down to a 'class war' and the Chartist Movement failed because the ruling class ultimately held the upper hand. They had all the resources on their side: the law, troops, police and money. The government could easily put down outbreaks of violence and insurrection. During the course of Chartism the government imprisoned or deported hundreds of agitators, including John Collins who spent twelve months in Warwick Gaol. It's perhaps an over-simplification, and it ignores improvements in the economy, but when O'Connor went under he took the Chartist Movement with him because he had ruled with absolute power, and thanks to him the crusade had lost much of its credibility.

Chartism was tainted by physical force advocates from the get-go, as was seen in the comments of Members of Parliament when the first National Petition was presented to the government. As one Member put it: "I am opposed altogether to every exertion of physical force in attaining these objects, more especially when I observe that those who stimulate the people to violence are most careful to remain at a distance when the army comes down upon the victims of their advice."

In the end Chartism boiled down to a 'class war' and the Chartist Movement failed because the ruling class ultimately held the upper hand. They had all the resources on their side: the law, troops, police and money. The government could easily put down outbreaks of violence and insurrection. During the course of Chartism the government imprisoned or deported hundreds of agitators, including John Collins who spent twelve months in Warwick Gaol. It's perhaps an over-simplification, and it ignores improvements in the economy, but when O'Connor went under he took the Chartist Movement with him because he had ruled with absolute power, and thanks to him the crusade had lost much of its credibility.

CHARTIST LEGACY

Although the Chartist Movement failed to achieve the desired reforms in the short term, it challenged the government of the day, educated the working man, and paved the way for future success. By 1918 five of the Chartists' six points of reform had come into law - the exception being annual parliamentary elections - and all of those through peaceful means.

It took the Fourth Reform Act (also known as the Representation of the People Act 1918) during the First World War before all adult men, including men in barracks and returning from war, became eligible for the vote, regardless of whether they owned or rented property. The 1918 Act also provided for women over 30 years to register to vote so long as they or their husband owned or rented property. Even then a small number of members in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords voted against it! Ten years later the Representation of the People's Act of 1928 enabled everyone over 21 years the right to vote.

Chartism had a hand in forming democracy as we know it today in the United Kingdom and other countries, but perhaps most of all Chartism showed future reformers and generations the enormous power of the people to initiate change.

It took the Fourth Reform Act (also known as the Representation of the People Act 1918) during the First World War before all adult men, including men in barracks and returning from war, became eligible for the vote, regardless of whether they owned or rented property. The 1918 Act also provided for women over 30 years to register to vote so long as they or their husband owned or rented property. Even then a small number of members in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords voted against it! Ten years later the Representation of the People's Act of 1928 enabled everyone over 21 years the right to vote.

Chartism had a hand in forming democracy as we know it today in the United Kingdom and other countries, but perhaps most of all Chartism showed future reformers and generations the enormous power of the people to initiate change.