EARLY YEARS

If you have landed on this page - the WELCOME PAGE a good place to start!

The history of the British Chartist Movement deservedly recognizes the names of men like William Lovett, Feargus O'Connor, John Frost, and James O'Brien (aka 'Bronterre'). Nevertheless, there are those individuals - such as John Collins, who is the subject of this website - who have been overlooked, or their achievements washed out by the more flamboyant and popular 19th century reformers and agitators.

|

John Collins and his selfless desire to improve the plight of the working class by campaigning for political reform and the people's right to vote puts him in the select company of the leaders of the Chartist Movement.

|

A BIRMINGHAM LAD

|

John Collins was born on 2nd December 1802 into a working class home on Navigation Street, in the heart of Birmingham, Warwickshire, England. Baptized at St Philip's Church on 2nd May 1803, he was the eldest of five surviving children of Joseph (a self-employed buckle-chaser) and Catherine 'Johnson' Collins - including James 1805-1873, Moses 1807-1827, Constance Catherine 1814-1820, and Thomas 'Johnson' Collins 1812-1888. Two other siblings died in their infancy.

On 3rd August 1821 John Collins married Hannah West in St Martin’s Church in the Bull Ring, Birmingham, and they had three children Joseph 1821-1891, Hannah 1824-1871, and John Jr 1827-1861. |

John Collins grew up during a time of economic depression with massive unemployment and many on short time who were subjected to poor pay and harsh working conditions. People lived hand to mouth selling their possessions in order to eat. The government was controlled by a wealthy elite, and the working class had little or no say in the running of the country or how their taxes were spent. Even after the Great Reform Act of 1832 the vast majority of the citizens of Great Britain did not have the right to vote.

|

The number of males in the United Kingdom age 21 and above was about 7,000,000, out of which the number of registered electors was a little over 1,000,000 - and amongst them the suffrage was unequally distributed [Sketches of Reforms & Reformers, p 303, Henry B Stanton]. With approximately one-seventh of adult males entitled to vote it constituted an early form of Catch 22: the law needed changing to give working class men the right to vote, but working class men did not have the vote (or representation in parliament) to get the law changed accordingly. Needless to say women did not have the vote at all.

|

EDUCATION

Like many youngsters of that era, John Collins started work at an early age, or as he once said: "... from the time he was very young he had worked for his bread." Children of the working class were expected to contribute to the family income, and at the age of seven Collins was forced to work in his father's buckle-chasing workshop. As a result John would have been familiar with the lack of time and opportunity for leisure and learning. Nevertheless, this was a boy of exceptional character and determination, and we know he read a great deal, or as he put it: "everything he could get his hands on."

Before the 1840s few children attended school, and those who did would have had to pay at least one penny a week for the privilege. For a working class family, barely able to put bread on the table, the cost of education would have been out of the question.

|

Because of this, Collins learned to read and write at Sunday School, together with his own nightly efforts. Although unlikely, it's possible he may have attended a "dame school" a few hours a week.

Dame schools were at the very bottom of the school spectrum, usually run out of a woman's home for the benefit of children of tradesmen and artisans who had begun to understand the need for education. |

Coming from a working class background, Collins recognized the disadvantages of the lower orders. He believed in education as a way to elevate the mind and the body, and in turn improve society as a whole. This was to be the theme throughout the book he co-wrote with William Lovett during their imprisonment in Warwick Gaol. And following his release from prison, Collins went on to establish the Chartist Church in Birmingham that provided Sunday schools and education for children and young men.

TOOLMAKER BY TRADE

Like his father before him, John Collins was a toolmaker. He was not a shoemaker, as various historians have claimed - including Hovell who said: "It is remarkable how many shoemakers failed to stick to their lasts" and incorrectly named Collins as one of them. The book Collins co-authored with William Lovett states quite clearly John Collins was a toolmaker.

When he was fourteen Collins left his father's business and became an apprentice to Ralph Heaton of Bath Street, Birmingham as a toolmaker and fitter. Co-incidentally, he trained with another apprentice by the name of Thompson who later headed the Birmingham Committee that organized the welcome dinner for Collins on his release from Warwick Gaol.

When he was fourteen Collins left his father's business and became an apprentice to Ralph Heaton of Bath Street, Birmingham as a toolmaker and fitter. Co-incidentally, he trained with another apprentice by the name of Thompson who later headed the Birmingham Committee that organized the welcome dinner for Collins on his release from Warwick Gaol.

|

After completing his recognized apprenticeship, John Collins became a toolmaker and fitter at Joseph Gillot's steel pen factory whose original, start-up premises (making hand made pens) were located in a garret on Bread Street (now Cornwall Street) Birmingham - which is the same street where the Collins’ family lived. Gillot took out a patent in 1831 for making pens using tools and machinery (The Story of the Invention of Steel Pens). Although we cannot know for sure, it is entirely possible that John Collins helped set up the first presses for Gillot's emerging business.

|

Collins is recorded as saying he earned a good living for himself and his family, and that he had been fortunate in his circumstances. As a toolmaker and fitter, he would have been able to make jigs, fixtures and tooling for mass production, as well as use the machinery on the factory floor. In a time of great industrial expansion his ability to work from drawings or verbal instructions would have made him an invaluable part of the shift in manufacturing from manual labour to machine operations. Collins would have been a well respected and an equally well paid operative.

EDUCATION AND RELIGION

|

During the time of his apprenticeship, Coolins took an active part in the Sunday school connected with Lady Huntingdon's, and when he was about twenty-four he was appointed local preacher of the town and neighbourhood including a small church in Harborne near Birmingham.

George Jacob Holyoake (the well-known writer, newspaper publisher and self-proclaimed atheist who first coined the term 'secularist') recalled walking to the church, as a boy, with his friend John Collins - and sitting through Collins' long sermons! Horse drawn buses did not service Harborne until 1838, so Collins and Holyoake would have walked the three miles from Birmingham to the ancient parish church of Harborne. |

|

Until the latter part of the 19th century there was no free (and compulsory) public education system in England. The wealthy and upper classes had access to governesses or expensive private schools, but the masses could not afford it.

Sunday schools that provided text books and bibles gave working class families an opportunity to learn to read and write for free. Thanks to the charity of the Church of England and Sunday School teachers like John Collins thousands of children from poor and working class homes received a form of "education." |

|

As a result of Collins' religious beliefs, his political speeches were frequently peppered with scripture. He was opposed to violence, and after touring Scotland (which had some two dozen or more Chartist Churches by 1842) and his term in prison, Collins became greatly influence by Christian Chartism, which combined temperance, morality and religion with a strong dose of social reform.

Together with another "moderate" radical, Arthur O'Neill of Scotland, John Collins established a Christian Chartist Church for working class people on Newhall Street in Birmingham (opened on Dec 27 1840) where Collins served as deacon and pastor [Northern Star 27 Mar 1841]. Eventually, there were a reported two Chartist Churches as well as worship conducted in fourteen houses in Birmingham [Cork Examiner 8 Oct 1841]. One of the many arguments against suffrage for the working class was their ignorance. Collins and O'Neill believed the Chartist Church, with its emphasis on education and self improvement, would help pave the way toward political reform and working class equality, |

In Defence of the Working Man's Reputation

In speaking at a dinner in his honour, following his release from prison, Collins observed: "that those who opposed the working classes, asserted that the greater part of the criminals of the country were working men, and that almost all the vice in the land was to be laid at their doors."

Rhetorically speaking, Collins asked why it was the working man was treated with such disrespect. To which he answered himself, it was because they never stepped forward to show their true qualities and abilities. He went onto explain it this way:

In speaking at a dinner in his honour, following his release from prison, Collins observed: "that those who opposed the working classes, asserted that the greater part of the criminals of the country were working men, and that almost all the vice in the land was to be laid at their doors."

Rhetorically speaking, Collins asked why it was the working man was treated with such disrespect. To which he answered himself, it was because they never stepped forward to show their true qualities and abilities. He went onto explain it this way:

|

"Who had been the authors and writers for the press of this country? Almost always the middle and the higher classes; these men were notoriously ignorant of the opinions and feelings and habits of the working classes. Who knew anything of the history of the working classes? Some books had been published with some pretensions of the kind; but they really contained nothing at all to the purpose; and he should not be surprised if a good history of the working classes should one day be published by one of themselves, and which would really deserve its title.

"Then, again, if there was any good thing done by any of the middle classes, it appeared in all the newspapers. If any of them gave a few pounds for a charitable purpose, everybody was sure to hear of it; but nobody heard of the kindly sympathies of the working man, for his unfortunate brother, when he sat whole nights by his sick bed, or when he clothed his ragged children, and shared his hard crust with his family. All this was done privately, and no noise was made about it, and therefore there was no idea on the part of the middle classes, that working men possessed any feeling or humanity. Thus all the good was attributed to the middle classes, and all the bad to the working classes." |

Collins also said the middle classes formed their ideas of working men from police and court reports, but he asked who were the thieves and bad characters? He assured the audience that during his time in Warwick Gaol there were quite as many of the middle class as the working class on trial, and Collins said he would never submit to hear the working man slandered without speaking in their defense, to which there was much cheering from the audience.

SETTING THE SCENE FOR CHARTISM

|

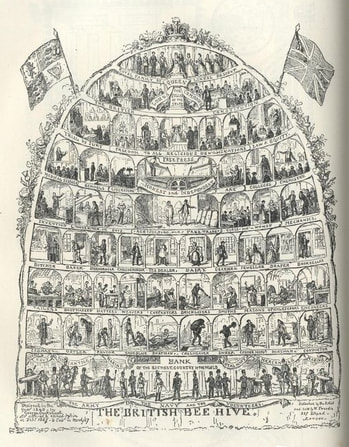

Industrial Revolution

The 1830s were called "The Times of Trouble" with good reason. The Industrial Revolution which began in Britain in the late 1700s brought about tremendous change and growth to Birmingham - and not always for the better. New inventions and equipment changed the face and pace of manufacturing. Whereas before people worked from home or in small shops (sometimes referred to as the cottage industry) putting out limited quantities of hand made goods, now they - and the country folk who migrated in droves from rural communities into towns - joined assembly lines in smoke-spewing factories producing a proliferation of goods on special machines. |

|

The Changing Landscape

Huge coal deposits in the nearby "Black Country," to the north and west of Birmingham, provided the necessary energy to drive the iron foundries and steel mills whose towering infernos turned the nighttime sky into a firey glow. Improved transportation opened up new markets. In Birmingham, as in other industrial centres, row upon row of cheap, back-to-back housing provided squalid accommodation for the massive influx of factory workers. The lower class poor struggled to survive in the slum-filled town with its dirt and pollution, and the upper and middle classes moved out to respectable areas and clean country air. |

|

Fellow Slaves

Collins equated the plight of working men (whose employers dehumanized them as "hands" or "labourers") with that of "white slavery," and in fact he was an abolitionist, along with such men as William Lovett. It was not unusual for Collins to address working men attending his meetings as "fellow slaves," and once, when speaking at a Chartist rally, Collins declared that the existence of slavery was the only stain on America's character, but that it did not come about from her own democratic institutions being a leftover of British rule. |

Explosion of Birmingham's Population

1648 5,472 1700 15,032 1750 24,000 1801 73,000 approx 1831 142,251 1841 182,922 1851 232,841 1871 342,505 [Population Statistics: Revolutionary Players maintained by West Midlands History] www.revolutionaryplayers.org.uk.about-us/

|

|

This then was industrialization, and making a profit was central to everything. "It was the best of times, and the worst of times!"

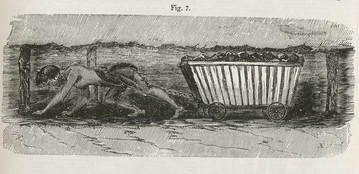

The wealthy manufacturers and property owners grew rich at the expense of the working class poor who worked long hours and earned a pittance. Women and children endured deplorable conditions in factories and down the mines. In the image opposite of a grim subterranean mineworks, notice the harness and chain between the child's legs pulling a trolley full of coal. |

GROWING SENSE OF INJUSTICE AMONG THE PEOPLE

Small wonder, then, that the poor and working class were disillusioned and angry with the (class) system and an indifferent government.

|

Collins hit the nail on the head when he once said, "Every interest was represented in the Legislature save and except the interest of the people. The church, the bar, the landed and monied interests, and all these interests flourished."

He went on to say: " Jack says to Tom, 'Will you assist me to pass this bill for the landed interest?' 'Certainly,' says Tom, 'if you will assist me in passing the other bill for the monied interest.' Jack attends to Tom's request, and Tom attends to Jack's, and between them the people are victimized." |

The Great (1832) Reform Bill

Collins wanted to change things for the better and during the agitation for the Great Reform Bill he became involved in all the movements of the day - in particular trade societies and the Birmingham Political Union [Birmingham Journal April 9 1842 p 4]. Without a doubt he would have been one of the 10,000 working men at the public formation of the Birmingham Political Union on 25 January 1830. Temperatures were among the worst that year: there had been a heavy snow and canals were frozen over. Nevertheless, working men such as John Collins answered the call for the unenfranchised "industrious classes" to join the Union's fight for political reform - which culminated in the passage of the 1832 Reform Bill (otherwise known as The Great Reform Bill).

Collins wanted to change things for the better and during the agitation for the Great Reform Bill he became involved in all the movements of the day - in particular trade societies and the Birmingham Political Union [Birmingham Journal April 9 1842 p 4]. Without a doubt he would have been one of the 10,000 working men at the public formation of the Birmingham Political Union on 25 January 1830. Temperatures were among the worst that year: there had been a heavy snow and canals were frozen over. Nevertheless, working men such as John Collins answered the call for the unenfranchised "industrious classes" to join the Union's fight for political reform - which culminated in the passage of the 1832 Reform Bill (otherwise known as The Great Reform Bill).

|

However, The Great Reform Bill with its promise of change to the political system actually did little or nothing for the lower classes of society.

There was a semblance of reform in that so-called "Rotten Boroughs" were removed, new towns were given the right to elect Members of Parliament, and those men who owned and occupied property worth at least £10 (or rented property worth £10) were given the right to vote. Such men who qualified for the franchise through 1832 Reform Act became known as the "ten pound voters." Essentially, the franchise was extended to the middle class who qualified due to their financial and propertied status. The working class poor - which the Reform Bill was supposed to help - were left out in the cold along with a growing sense of discontent. That discontent was echoed in the words of the Yorkshire activist Abraham Hanson when he said the working class "were nothing in a political sense but the mean slaves and serfs of the aristocracy of the land and the aristocracy of the spindle." |

No Representation

Without the vote, the lower orders in society had no representation in the halls of power. There was no one to speak for them, no one to air their grievances and certainly no one to pass laws that benefited the working class population. Even the Birmingham Political Union (BPU) that represented the working class and fought for political reform ceased to function after playing a role in the passage of the not so "Great" 1832 Reform Bill.

Without the vote, the lower orders in society had no representation in the halls of power. There was no one to speak for them, no one to air their grievances and certainly no one to pass laws that benefited the working class population. Even the Birmingham Political Union (BPU) that represented the working class and fought for political reform ceased to function after playing a role in the passage of the not so "Great" 1832 Reform Bill.

Poverty & The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834

John Collins was particularly affected by the poverty of the working class which he observed in the misery and unhappiness of his own neighbours. In speeches he talked of witnessing numerous funerals of those who "died of want," and said no man could view the present state of the working class with indifference. He blamed a corrupt and self-serving government made up of wealthy and landed gentry who made laws to suit themselves, whilst the working families of Birmingham and the industrial north starved on the streets in filth and muck.

John Collins was particularly affected by the poverty of the working class which he observed in the misery and unhappiness of his own neighbours. In speeches he talked of witnessing numerous funerals of those who "died of want," and said no man could view the present state of the working class with indifference. He blamed a corrupt and self-serving government made up of wealthy and landed gentry who made laws to suit themselves, whilst the working families of Birmingham and the industrial north starved on the streets in filth and muck.

|

To add insult to injury the government introduced the draconian Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834. Its purpose was to cut funding for the poor thereby encouraging people to work and deterring malingerers from seeking help. The reality of it was it penalized and stigmatized the truly unemployed and destitute families. Those paupers who did apply for help were treated like common criminals, being separated from family members and forced to live and work in the grim and dreaded workhouse or poor house.

Workhouses became crammed with people sleeping eight to ten, head to foot, in one bed. It was that or starve to death. Not unnaturally, workhouses (also called the "New Bastilles") were perceived as a kind of prison. But perhaps most of all, the humiliating 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act served to exacerbate the brewing social discontent among the mass of working class people. |

In 1836 recession hit not just Birmingham and the surrounding Midland Counties but the whole of Britain. Trade was down, unemployment up, and those who had jobs were sorely mistreated. People lived and died in cramped, dilapidated and unsanitary housing that lacked running water and decent toilet facilities - and still the mass of British working class people didn't have the right to vote. Industrialists adopted a laissez-faire attitude, the government looked the other way. Workers had no say over local factory conditions or housing standards, never mind a voice in the running of the country or how their taxes were spent.

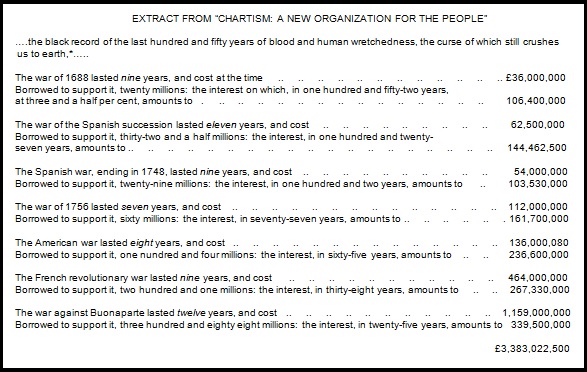

Meanwhile, people's grievances mounted. They perceived a government that reneged on its support for the poor and unemployed, but expected them to bear the cost of enormous National Debt and loss of life brought about by the wars with America and France some twenty years before. America (1812-1815) and France (1793-1815) The Battle of Waterloo in 1815 cost the lives of 15,000 British men.

The Burden of Tax - As Laid Out by William Lovett & John Collins

The extract below is from the book Chartism: A New Organization of the People written in 1840 by William Lovett and John Collins whilst imprisoned in Warwick Gaol. It shows the terrible burden of tax on the working class brought about from the previous 150 years.

The extract below is from the book Chartism: A New Organization of the People written in 1840 by William Lovett and John Collins whilst imprisoned in Warwick Gaol. It shows the terrible burden of tax on the working class brought about from the previous 150 years.

In the words of that friend of the people, radical Member of Parliament John Fielden, in a speech at Peep Green "The (1832) Reform Act has proved a complete failure." Henry Brewster said: "....her (Great Britain's) huge national debt, and her immense annual expenditures crush her labouring masses between the upper and nether millstones of remorseless taxation and hopeless poverty."

Or, as John Collins put it: ".....there can be no security for the people until they have the right to vote."

Or, as John Collins put it: ".....there can be no security for the people until they have the right to vote."

JOHN COLLINS - COMING OUT IN A PUBLIC CAUSE

Revival of the Birmingham Political Union

With the deepening economic recession that heralded the "Hungry 40s," the former council of the Birmingham Political Union (BPU) saw the failure of the 1832 Reform Bill together with increasing public discontent as an opportunity to revive the Union that had closed its doors some years before.

With the deepening economic recession that heralded the "Hungry 40s," the former council of the Birmingham Political Union (BPU) saw the failure of the 1832 Reform Bill together with increasing public discontent as an opportunity to revive the Union that had closed its doors some years before.

|

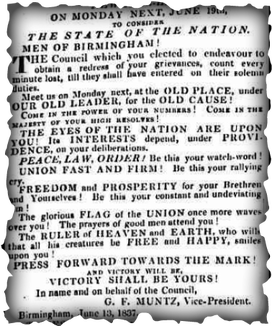

On 16 June 1837, with some 8,425 newly enrolled members, the council of the BPU agreed they should petition the Houses of Parliament for repeal of certain money laws as well as five demands: household suffrage, voting by ballot (as opposed to a show of hands), triennial parliaments, the abolition of property qualifications for Members of Parliament and a wage of attendance for MPs. [The Chartist Movement, Mark Hovell]

In their previous life the BPU council consisted a group of middle class businessmen with a deep rooted currency agenda. They, especially their leader Thomas Attwood, believed that unlimited paper money would solve the country's social misery. The BPU represented the working class even though none of that class was amongst its leaders. This time around they knew they had to do things differently, except they never quite learned from past mistakes and they began by electing yet another council made up of wealthy businessmen!

|

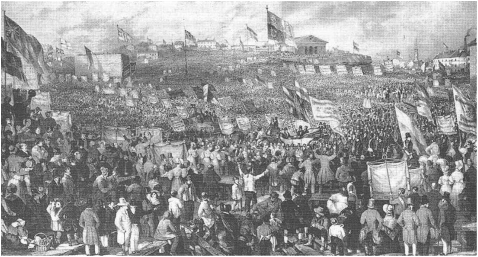

In spite of the council's middle class leadership, their appeal to the public to attend a meeting on Newhall Hill in Birmingham brought out thousands of people who were angered by the riches of the few, the poverty of the many, and a government that didn't seem to care.

|

Newhall Hill - 19th June 1837

|

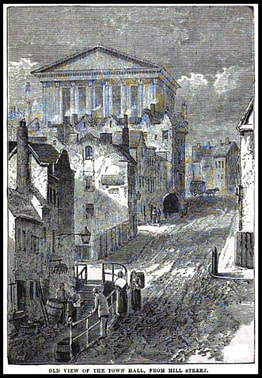

It was a warm summer day when the procession set off from the Bull Ring, and by the time it reached Bennett's Hill the whole of New Street from the Town Hall to the High Street was one dense mass of people. Then it was onto Newhall Hill, which was the place of previous mass meetings.

33 year old John Collins would have been in that crowd of 50,000. He, and the cheering crowd, would have heard Union leaders talk of uniting 'two million men' in support of a National Petition for political reform, and if all else failed hints of a possible general strike! (Birmingham Journal 24 June 1837). |

This was all well and good, except the middle class leaders on the council of the Birmingham Political Union, including Thomas Attwood, were not true radicals or agitators. They were men who saw themselves as the "generals" directing a crusade rather than actively taking part in it. They wanted and needed allies in Scotland and the North of England where the working classes were in great distress. These middle class "generals" were unwilling to cultivate them. Enter John Collins, working class man.

|

John Collins Elected to the Council of the Birmingham Political Union

On 4th July 1837, two weeks after the Newhall Hill revival, John Collins was present when the BPU council met in the Birmingham Town Hall. Their first order of business was a proposed letter of condolence to the Dowager Queen Adelaide on the death of the King and praise for the conduct of the new, young Queen Victoria.

The council's last order of business was the election of John Collins of Bread Street to the council, which broke with tradition and made him the first working class man to sit on the council of the Birmingham Political Union. It was a good move for the BPU and the ensuing Chartist Movement in that it brought on board a working class "disciple" who turned out to be a man of exceptional character and speaking skills. Thus began the Age of Victoria - and John Collins' radical career. He was re-elected to the BPU council the following year. |

THE JOINING OF RADICAL FORCES - BIRMINGHAM & LONDON

At first the newly revived Birmingham Political Union attempted to go it alone on the battleground for political reform. John Collins campaigned on behalf of the Union in Birmingham and neighbouring towns while the middle class leaders of the Union ignored overtures from the London Working Men's Association (LWMA) that had been formed in 1836 by William Lovett cabinet maker, Henry Hetherington newspaper publisher, and others. The LWMA was a much smaller and quieter organization of limited membership. It was working on its own petition including universal suffrage which would later become the "People's Charter" consisting their six principals for political reform.

|

Approaches (in June and October 1837) made by the BPU leaders to the Premier Lord Melbourne and the Chancellor of the Exchequer Mr Rice regarding the people's grievances and the BPU's old agenda of currency reform were ignored by those two government men. Thomas Attwood proved to be an absentee figurehead of the Birmingham Political Union spending most of his time in London, and to cap it all membership in the newly revived BPU began to fall off as it became clear the Union alone did not have (and possibly never did have) the guns and ammunition to win a fight in the national arena.

|

The old-time (middle class) Union leaders were finally forced to face what they already knew: they were never a national organization; they could not succeed without nation-wide support and recognition; and they had to drop their crusade for monetary reform. Though in fact Thomas Attwood continued to pursue monetary reform while he was resident in London.

|

Meanwhile, in London and the provinces Working Men's Associations were formed in 1837, and the Birmingham Men's Memorial Committee (Collins chaired their fund raising wing) threw in their lot with the BPU. Speaking at a town meeting of the two organizations in October 1837 to discuss distress in Birmingham, Collins issued a warning of a point beyond which it was not right for the government to oppress the working people. [Chartist Experience, J Epstein & D Thompson]

|

In the December of 1837 the Birmingham Political Union formally announced they now stood for universal suffrage (as opposed to household suffrage) and democracy, and they famously advertised that the men of Birmingham were willing to lead or follow!

The London Working Men's Association (with its membership of a few hundred) immediately responded favourably, thus forming an alliance between the BPU and the LWMA that ultimately led to the nationwide Chartist Movement. Meanwhile 'up North' a radical by the name of Feargus O'Connor bought the Northern Star and Leeds General Advertiser that was destined to become Chartism's most powerful and firey mouthpiece - not unlike its owner.

The London Working Men's Association (with its membership of a few hundred) immediately responded favourably, thus forming an alliance between the BPU and the LWMA that ultimately led to the nationwide Chartist Movement. Meanwhile 'up North' a radical by the name of Feargus O'Connor bought the Northern Star and Leeds General Advertiser that was destined to become Chartism's most powerful and firey mouthpiece - not unlike its owner.

|

In early 1838, at a meeting of the Birmingham Political Union, John Collins told his fellow council members he had visited working class families on one street in the town, and out of some fifty families only one was living in relative comfort.

|

Political action was slowly beginning to escalate, and with it the dawn of the Chartist Era and John Collins' political career.

Navigation Tips:

- Use the Menu Bar at top of each Page to follow the John Collins' story in chronological order.

- Go to the Content Page to browse all the Pages on the entire website.

- The Welcome Page gives an overview of the life and times of John Collins. I recommend you start there.

- The purple button will take you to the top of this Page.

Proudly powered by Weebly