"CHARTISM: A NEW ORGANIZATION OF THE PEOPLE"

By William Lovett, Cabinet-Maker & John Collins, Tool-Maker

Click on any image above to enlarge it |

|

On the first Monday in September 1840, thousands had assembled on Holbeck Moor in Yorkshire to welcome and honour John Collins and two other Chartists, all of whom had been recently released from gaols in different parts of the country. (In a government clampdown on the Chartist Movement, Collins had been imprisoned for one year for Libel and Sedition following the Bull Ring Riot on 4 July 1839.)

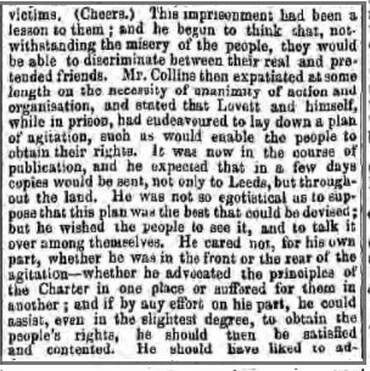

In an open carriage the three men were escorted into Leeds in a procession that stretched three quarters of a mile. They headed to the Hall of Science where dinner was laid on for the distinguished guests. In the course of John Collins' speech (extract from the Northern Star to the right) at the dinner he said that while he was in Warwick Gaol, he and William Lovett had written what he called "a plan of agitation" that was to be published in a few days. That plan of agitation was their famous work entitled "Chartism : A New Organisation of the People." |

|

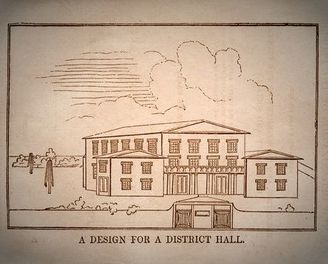

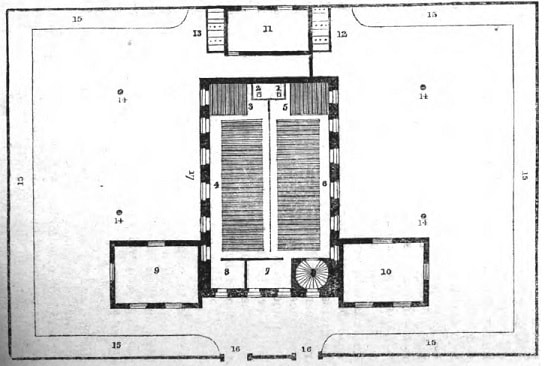

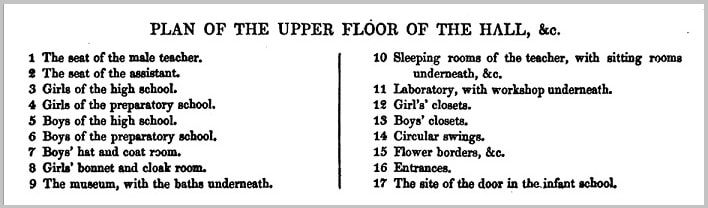

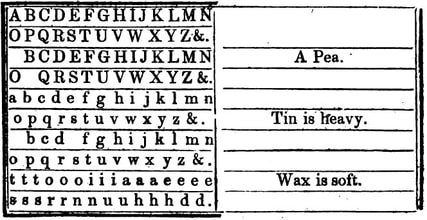

"Chartism: A New Organisation of the People" proposed a National Association of the United Kingdom for the purpose of politically and socially improving the people. Ahead of the times, the book called for a national educational scheme for children and adults including schools and halls, circulating libraries, teacher training, tracts, and missionaries.

The book admits many of the working class would be unwilling or unable to help fund such a program. Nevertheless, it showed that if those 1,283,000 individuals who signed the Chartists' 1839 National Petition paid four shillings a year it would be possible to establish 80 halls or schools, over 700 circulating libraries, 4 missionaries, 20,000 tracts, and sundry expenses each year. |

The following is the complete text of the 1841 edition of "Chartism: A New Organisation of the People" by Wiilliam Lovett and John Collins - including its "British English" spelling (such as honour, colour, centre, mitred, etc) and certain mis-spellings (such as phrenzied, glueing, trafficing, develope, etc). For ease of reading, each footnote appears at the end of its relevant paragraph.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~