CHARTIST LEADER

If you have landed on this page - the WELCOME PAGE a good place to start!

THE DAWNING OF THE CHARTIST ERA

|

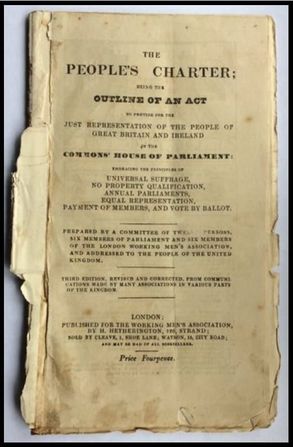

THE PEOPLE'S CHARTER

Being the outline of an act of parliament embracing "the six cardinal points of Radical Reform."

|

A pro-Chartist pamphlet entitled "The Question 'What is a Chartist?' Answered" was published by the Finsbury Tract Society in 1839 for 1s. 6d per hundred, or five for a penny. It offered answers to popular Chartism questions posed by a "Mr Doubtful."

SPOKESMAN FOR THE BIRMINGHAM POLITICAL UNION

In early 1838 the BPU council approved a plan for extending their reach beyond Birmingham and the Midlands. Toward that end they appointed fellow council member John Collins their "emissary" charged with the onerous task of recruiting the working men and radicals of Scotland and the North.

The focus of this "holy and peaceful pilgrimage," as it was later called, was the major town of Glasgow with its large, incredibly distressed working class population. Collins' job was to pave the way for a great demonstration in that town at which a delegation from Birmingham would launch a nationwide crusade for the BPU's National Petition. The Petition included the same six demands as The People's Charter including annual (rather than triennial) parliaments which was the radical measure John Collins advocated (Fife Herald 19 April 1838) and convinced the Union to adopt.

Thomas Attwood, the founder of the Birmingham Political Union, lived in London and rarely visited Birmingham. The other council members of the Union were middle class men with business interests. None were willing or able to sacrifice their time for such an undertaking of agitation in Scotland. In the event of its success, they - especially Attwood - would marginalize Collins and take all the credit for it.

The focus of this "holy and peaceful pilgrimage," as it was later called, was the major town of Glasgow with its large, incredibly distressed working class population. Collins' job was to pave the way for a great demonstration in that town at which a delegation from Birmingham would launch a nationwide crusade for the BPU's National Petition. The Petition included the same six demands as The People's Charter including annual (rather than triennial) parliaments which was the radical measure John Collins advocated (Fife Herald 19 April 1838) and convinced the Union to adopt.

Thomas Attwood, the founder of the Birmingham Political Union, lived in London and rarely visited Birmingham. The other council members of the Union were middle class men with business interests. None were willing or able to sacrifice their time for such an undertaking of agitation in Scotland. In the event of its success, they - especially Attwood - would marginalize Collins and take all the credit for it.

|

So while the council of the BPU sat back and awaited results, the task of preparing Scotland to join the Chartist Movement was more or less left to John Collins. Luckily, he proved to be an energetic and skillful speaker in the same league as Vincent, Taylor, Lowery and O'Connor. By April 1838 Collins was reporting a highly successful tour of Scotland.

|

|

In 1838 ".... John Collins reported to the Birmingham Political Union that they had political unions in Bradford, Coventry, and in Scotland, but soon they would have unions in all the major town."

Alexander Wilson, Chartist Movement in Scotland |

"In 1838 a rapid mobilization of the working classes was the outcome of the preparation of the Charter and National Petition and of the foundation of the Chartist press. The whole populace seethed in a state of fermentation."

Max Beer, History of British Socialism. |

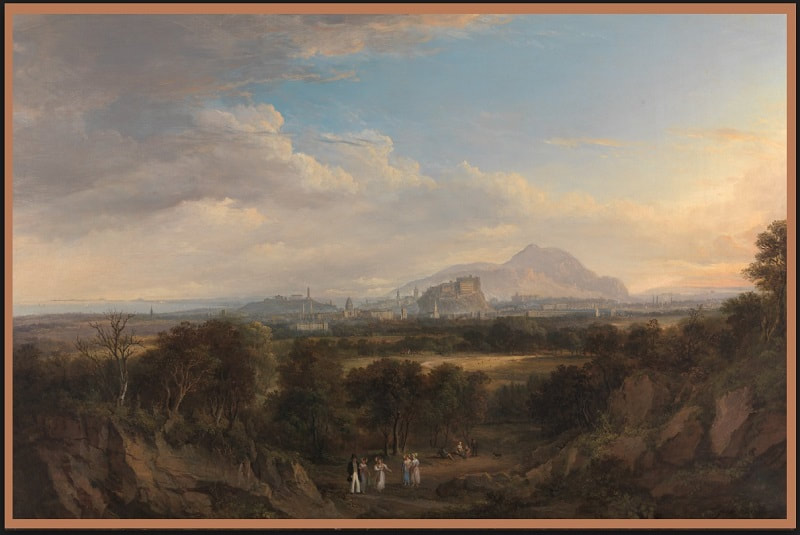

COLLINS ROUSES THE SCOTTISH LOWLANDS

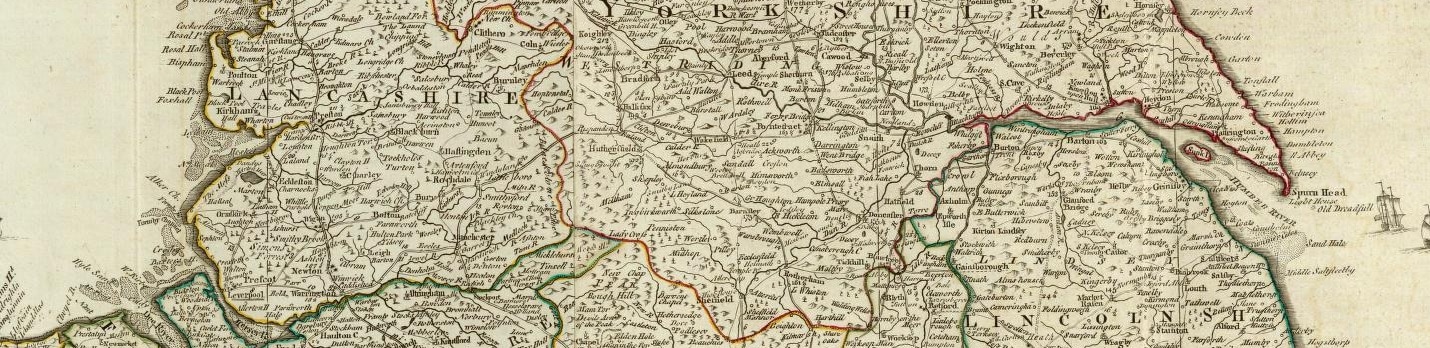

The mission to Scotland was uncharted territory for John Collins, both literally and figuratively. Coming from the working class he was not a well-traveled man, plus there was no motorized transport in those days. Railways had only just started, and going by road had its challenges.

|

Collins would have traveled north on a horse drawn stage coach. It would have been quite precarious sitting outside on the top of a speeding, swaying conveyance, and even worse if it was raining. If he had the money he might have paid the extra to sit inside. The BPU council had agreed to pay him for his work [Birmingham Political Union p 133, Flick].

Additionally, Collins was a comparative newcomer to the political scene. His previous experience in public speaking was limited to that of local preacher and Sunday school teacher - and lately political debates and meetings within his home ground of Birmingham, Coventry, and the Midlands. |

SCOTTISH CAMPAIGN TRAIL & LEADING THE CHARGE FOR THE CHARTIST MOVEMENT

The pressure on John Collins to rally the crowds of would-be Scottish supporters must have been enormous, especially given it had been many a year since Scotland had seen large political gatherings. Nevertheless, with his memory for facts and figures, and his own form of persuasive "speak" he was more than up to the challenge.

|

Unlike the mostly middle class council members of the Birmingham Political Union, Collins had the advantage of coming from a humble, working class background that resonated with the trade unions and the common man he had come to recruit.

He was "one of them." He was straightforward and honest, and he was sincere in his desire to change things for the better - all traits appreciated by the traditionally dour and taciturn Scotsmen living in abject poverty. Collins was the perfect spokesman for the newly emerging reform movement, and people came out in their thousands to hear him speak. |

|

Collins encountered great support in Edinburgh and Dundee, as well as successful visits over many weeks at Paisley, Barrhead, Kilbarchan, Strathaven, Johnston, Beith, Kilburnie, Houston, Lochwinnoch, Parkhead, Ayr, Glasgow (more than once), Kilmarnock, Newmilns, Mauchline and Cumnock - the list goes on and on.

He met with local radicals, gave rousing speeches before huge, organized crowds, and departed those venues with much fanfare (bands and flags) and literally thousands of cheering inhabitants. |

He attended as many as three meetings a day. In one such place he was escorted in grand style in a carriage driven straight down the middle of the main street. At another, in Bridgeton he gave a speech to a gathering that included three hundred specially invited ladies. Click here to read letters on Collins' progress in Scotland.

Carrying the Faith

Not one to rest on his laurels, Collins was still carrying the faith for universal suffrage and the National Petition in the final days leading up to the grand finale of the great Glasgow Demonstration. The Saturday before the big day, he addressed a meeting at Canniesburn Toll at which some 5,000 people poured in from nearby places such as Duntacher, Milngavie and Maryhill to hear him speak. It was a similar story when Collins addressed a crowd on Calton Hill. His status verged on that of visiting celebrity, the herald of hope and good news. The historian Gammage described Collins as a veritable "John the Baptist" for bringing Scotland's radicals and trade unions into the fold of England's emerging Chartist Movement.

Not one to rest on his laurels, Collins was still carrying the faith for universal suffrage and the National Petition in the final days leading up to the grand finale of the great Glasgow Demonstration. The Saturday before the big day, he addressed a meeting at Canniesburn Toll at which some 5,000 people poured in from nearby places such as Duntacher, Milngavie and Maryhill to hear him speak. It was a similar story when Collins addressed a crowd on Calton Hill. His status verged on that of visiting celebrity, the herald of hope and good news. The historian Gammage described Collins as a veritable "John the Baptist" for bringing Scotland's radicals and trade unions into the fold of England's emerging Chartist Movement.

|

Collins' forthright and passionate speaking style was founded on a lifetime of witnessing deprivation, squalor and wretchedness on the streets of Birmingham. That, together with his use of scripture and amusing anecdotes with a political twist, made Collins a man worth listening to. People came in droves to hear him speak. Thanks in large part to him, England won the large scale support of the Scottish laborers of whom he once wrote "there is misery enough, and intelligence enough, and zeal enough in Scotland alone ..."

|

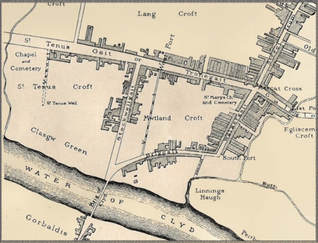

THE GREAT DEMONSTRATION AT GLASGOW GREEN

Collins’ successful and exhausting Scottish campaign culminated in a trades conference. This in turn led for calls by the trade unions for a massive radical demonstration in Glasgow in support of the National Petition and its plan of action. Thanks to Collins' efforts, a delegation from the Birmingham Political Union was formally invited to attend the Glasgow meeting. And what a spectacle the Glasgow Demonstration was: banners and flags flying above the heads of the various trades represented; bands playing lively airs; and an estimated crowd of 150,000 or more assembled on Glasgow Green for the arrival of the delegation of "Brummagem Lads" from the Birmingham Political Union with their National Petition demanding universal suffrage and much needed parliamentary reform.

|

The Commencement of the Chartist Movement

The meeting at Glasgow Green (at which some 3,000 colliers were said to attend) was one of the first large-scale demonstration of the Chartist Movement, and when the Birmingham delegation - consisting Thomas Attwood and the other BPU leaders - stepped onto the hustings (raised platform) on 21 May 1838 they were virtually guaranteed a grand and receptive welcome due in large part to John Collins' incredible recruiting mission. He had even forewarned the Birmingham leaders they would not be sent for if there was any doubt about its success. |

However, the Great Glasgow Demonstration was everything the Birmingham delegation could have hoped for. Quite possibly it even took them by surprise, given that they (other than Collins) had not taken one step into Scotland before. When they had departed Birmingham, they had little going for them. There was no great "send off" and a planned procession to the railway station had to be called off for lack of interest. [Thomas Attwood the Biography of a Radical, David Moss] . The delegation was reportedly somewhat depressed as they traveled to Glasgow, but on their arrival a procession two miles long and forty-three uniformed bands changed all that!

|

At the demonstration on the Green there were resolutions condemning the outcome of the 1832 Reform Bill; the BPU's National Petition was presented for approval and signatures of the Scottish people; and representatives of the London Working Men's Association announced they had drawn up a "Charter" that incorporated the demands of the BPU's National Petition as well as some additional points.

The monster crowd on the one hundred acre site was told the men of Birmingham were revived and ready to lead again. That they would petition, and petition, and petition again! And if the government dared to ignore the prayers of a famed "2 million men," Thomas Attwood told the cheering crowd he would call a National Strike. |

Feargus O'Connor's newspaper The Norther Star reported the great meeting at Glasgow Green was equal to most of those ever memorable exhibitions that took place about the passing of the 1832 Reform Bill. Interestingly, however, John Collins does not appear to have spoken or taken part at this great meeting, a fact also pointed out by Carlos Flick (Birmingham Political Union, p139). Since Collins was the only working man on the BPU council it is entirely possible Attwood and the other middle class leaders, with their ingrained feelings of superiority, chose to exclude him.

On the other hand, could it be the newspaper reporters simply overlooked John Collins' participation at the Glasgow Demonstration? This is extremely unlikely since Collins was a highly popular and newsworthy agitator. It was said he drew greater crowds than those two famous gentlemen Feargus O'Connor and Daniel O'Connell !

HERO OF THE DAY AT GLASGOW GREEN

|

John Collins was undoubtedly the (unsung) hero of the day at the Glasgow Green Radical Demonstration in that he majorly helped bring together the Birmingham Political Union, the radicals of Scotland, and the first public appearance of the LWMA "People's Charter" in Scotland.

Without his tremendous efforts who can say whether or not those three major forces would have come together or cooperated at that particular point in time. Certainly it was John Collins alone who did all the groundwork necessary to unite them. Even Thomas Attwood (the mostly absentee figurehead of the BPU) admitted he had never been an agitator, and that the Glasgow Demonstration was the first political meeting he ever attended outside of Birmingham. |

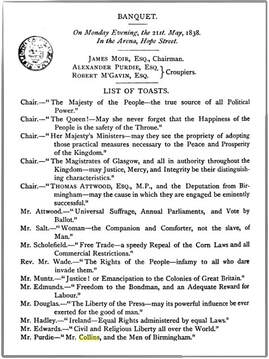

That evening at a banquet for several hundred at The Arena , Hope Street, Glasgow there were grandiose and long-winded speeches from the Birmingham leaders but still no record of the "Brummagem lads" actually thanking or acknowledging the tireless efforts of their own man (John Collins) who had helped make Scotland possible. He did all of the footwork, took none of the glory, and his contribution toward jump-starting Chartism as a 'national movement' was seemingly overlooked by his fellow BPU council and countrymen.

|

Again, one has to wonder about that apparent "slight." The BPU, especially Thomas Attwood, had a history of taking centre stage, claiming the success of others for their own and studiously ignoring the contributions of others.

Ever the opportunist, Attwood subsequently told Parliament that he went to Glasgow for the purpose of trying the feelings of the men of Scotland. This of course was not strictly true. He did go to Glasgow - but only after John Collins had already established Scottish sentiments and paved the way to success. Thomas Attwood took the credit that really belonged to John Collins. |

|

As it turned out some of the limelight fell on Collins when the local Glasgow chairman, James Purdie, showed appreciation on behalf of the men of Scotland and proposed a toast to "John Collins and the men of Birmingham" at the very end of the Hope Street banquet that evening. The proposal was greeted with several rounds of applause.

There were others too, who recognized Collins' contribution to the reform movement in Scotland. He was made an Honorary Member of the Glasgow Suffrage Association along with the well-known Francis Place and William Lovett. Some two years later, Scottish representatives, including Arthur O'Neill (who eventually relocated to preach in John Collins' Chartist Church in Birmingham) journeyed to Birmingham to honor Collins on his release from Warwick Gaol where he had been held political prisoner for twelve months. |

Grand Renfrewshire Meeting 1838

|

The day after the Great Glasgow Demonstration three of the Birmingham delegates, John Collins, Thomas Attwood and George Edmunds, attended the Grand Renfrewshire Meeting on the sacred grounds of Eldeslie, the reputed birthplace of that Scottish hero Sir William Wallace.

It had rained incessantly since the day before and the delegates were an hour late for the meeting having spent the morning receiving representatives from various Scottish towns, many of whom Collins undoubtedly would have met before. Nevertheless, when the Birmingham trio finally arrived at Eldeslie they were escorted by an "enthusiastic" crowd to an outdoor venue some four miles into the countryside. |

|

The procession included people from seventeen towns and trades together with numerous bands, some in uniform and some who had traveled many miles the day before, and in spite of the inclement weather 20,000 turned up for the meeting. Compared to the tens of thousands at the Great Glasgow Demonstration, the Renfrewshire meeting was considerably smaller. Nevertheless, it showed enormous support for the Birmingham men and the Chartist Movement that these many people were willing to walk four miles in the pouring rain to the grounds of the country estate loaned for the occasion by Mr Campbell Snodgrass, a local coalmine proprietor.

The meeting itself was conducted along much the same lines as Glasgow with speeches and approval for the National Petition. Afterwards, Collins and his colleagues were entertained by Snodgrass in his country mansion, where they toasted the renowned Wallace. Then it was onto Paisley for an evening party with several hundred ladies and gentlemen. |

COLLINS HEADS FOR THE NORTH OF ENGLAND

|

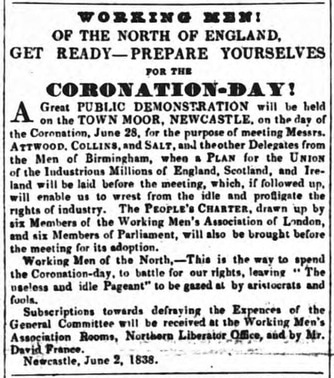

Newcastle-on-Tyne - June 2nd

Following the success of the Great Glasgow Demonstration and Eldeslie our indefatigable John Collins headed to the north of England stopping off in Newcastle-on-Tyne on 2nd June 1838 to drum up support for yet another massive outdoor meeting on the nearby Town Moor. Scheduled for June 28th, it would coincide with Queen Victoria's Coronation Day.

In announcing the Town Moor meeting and the Birmingham speakers - including John Collins - The Northern Liberator took the opportunity to remark on the burden of taxes on the poor and working class, as well as the immense cost of the Coronation versus the starving millions of British and Irish people. |

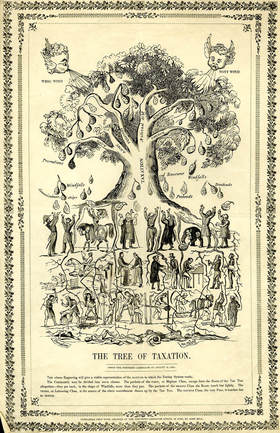

The Tree of Taxation

An engraving published in the Northern Liberator gave its readers a visible representation of the unfair tax system! The top, Highest Class, escape from the Roots of the Tax Tree altogether.They get back, in the shape of Windfalls, more than they pay. The Second Class, the Roots touch but lightly. The Third, or Labouring Class, is the source of the whole nourishment drawn up by the Tax Tree. The Fourth Class, the very Poor, it touches but to destroy. |

Sunderland in the District of Tyne & Wear - June 4th 1838

Like all the top orators of the day, Collins had the ability to convey a message and engage an audience at the same time. Nowhere is this more evident than at a Sunderland meeting on 4th June 1838 where he gave a clever and humorous speech, much to the amusement of the crowd. (Thomas Attwood was invited but bowed out.)

|

Excerpt from Collins' Speech at Sunderland

"Some time ago — and this was another instance of legislative wisdom — a committee was appointed to inquire into agricultural distress. Well, they came to the sage resolution that distress was caused by a superabundance of food, and commenced the cure by throwing 100,000 quarters of corn into the sea. "There was another committee appointed to inquire into the distress of the hand-loom weavers, and they (the committee) came to a conclusion that it arose from over-population, and recommended that £10 to £15 a-head should be expended in removing people to South Australia. "Thus they found too many mouths on the one side, and too many loaves on the other — (loud cheers and laughter) — but then they proceeded to legislate so as to keep the mouths and the loaves from coming together! It was high time that such fools were plucked from their usurpation!" John Collins - 4 June 1838 |

By illustrating a government that was run by men lacking in good judgement and commonsense, Collins showed the hypocrisy of a government that denied the working class the right to vote because it considered them uneducated and "unfit." Following Sunderland, Collins immediately went onto Leeds which was the stamping ground of Feargus O'Connor and home of his newspaper The Northern Star.

THE GREAT NORTHERN UNION & THE NORTHERN STAR NEWSPAPER

If it was John Collins who successfully stirred up Scotland and ventured into the textile enclave of the North of England promoting universal suffrage and adoption of the Birmingham-led National Petition, it was Feargus O'Connor who formed the Great Northern Union in competition with - or to offset - the power and leadership of the Birmingham Political Union and the London Working Men's Association. Whereas the BPU and LWMA were for the National Petition and the People's Charter, Feargus O'Connor was for unity and alliance between all three organizations - but preferably under his leadership.

Both the Birmingham Political Union and the London Men's Working Association stood for peaceful methods, such as mass rallies and petitioning, to obtain reform. The Great Northern Union (GNU) had little faith in petitioning for reform - a message and a difference that came out loud and clear when O'Connor published guidelines for membership to the GNU. In May 1838, prior to the formation of the GNU on 5th June, O'Connor said in no uncertain terms that every member should understand the difference between "moral force" and "physical force" and that in the event of moral force failing to obtain the desired reform, physical force would be necessary. It led to the militant catchphrase "Peaceably if we can, Forcibly if we must."

Both the Birmingham Political Union and the London Men's Working Association stood for peaceful methods, such as mass rallies and petitioning, to obtain reform. The Great Northern Union (GNU) had little faith in petitioning for reform - a message and a difference that came out loud and clear when O'Connor published guidelines for membership to the GNU. In May 1838, prior to the formation of the GNU on 5th June, O'Connor said in no uncertain terms that every member should understand the difference between "moral force" and "physical force" and that in the event of moral force failing to obtain the desired reform, physical force would be necessary. It led to the militant catchphrase "Peaceably if we can, Forcibly if we must."

|

In spite of the differences between the threesome, consisting the BPU, LWMA, and GNU, they were all in accord with the need for reform. At this point in time they recognized the need for each other. They were stronger together than on their own. At the June 5th meeting and official formation of the northern unions into one Great Northern Union held on Hunslet Moor, just outside Leeds in Yorkshire, John Collins of Birmingham was welcomed as one of the main speakers.

The other leaders of the Birmingham Political Union chose to stay away - Collins being the only one brave enough to attend O'Connor's physical force stronghold [Thomas Attwood: The Biography of a Radical by David Moss] . The BPU's National Petition was adopted at that June meeting, and Collins spoke of his missionary tour since the Great Glasgow Demonstration to launch the Petition, and plans for more mass meetings throughout the country. O'Connor moved a vote of thanks to Collins, and O'Connor pledged his support on behalf of Leeds and the North, thereby linking himself and the newly formed GNU to the men of Birmingham and their National Petition. |

O'Connor Caused Mischief within the Chartist Movement

Nevertheless, it proved to be an uneasy alliance, and there is no doubt that Feargus O'Connor (and his newspaper which played a huge part in his rise and takeover of the Chartist Movement) undermined the Birmingham Political Union. He usurped their meetings and divided the men of Birmingham. He caused similar dissention in Scotland (Chartist Movement in Scotland, Alexander Wilson) .

|

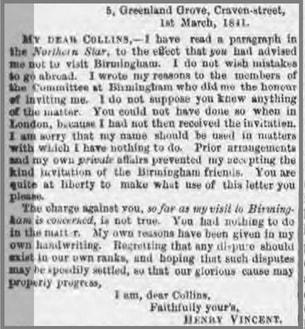

O'Connor published critical and inflammatory articles about moderate (moral force) Chartist leaders, and on more than one occasion he published lies about John Collins (Henry Vincent 1st March 1841), even charging Collins with being one of the most physical force men (Northern Star 8th May 1841). Nothing could have been further from the truth, and through his smear campaign O'Connor totally shattered Lovett and Collins' 'New Move' and 'National Association' attempts to educate the working man and unite the classes.

Feargus O'Conner once said his newspaper was the way to keep the "party" together and for everyone to know what was going on. It could justifiably be said he used The Northern Star to attack and destroy those reformers who showed independent action or challenged O'Connor's leadership. |

|

"The Chartists, unlike the Radicals, must be reckoned not only a separate political group but a separate political party. They (the Chartists) stood quite independent of the Whig and Tory organizations, and maintained a party machinery of their own.

"The general politics and tactics of the (Chartist) party were determined in conventions of delegates chosen by local Chartist associations, and their execution was left to a permanent executive committee and to paid lecturers and propagandist agents. "The organization was the product of a merger between the London Working Men's association, led by William Lovett and Henry Vincent; the Birmingham Political Union, including John Collins; and the political unions organized by Feargus O'Connor." (Preston W Slossom, Decline of the Chartist Movement ) |

SHEFFIELD AND CHARTIST MEETINGS IN OPEN AIR PLACES

Following the grand meeting at Leeds, Collins continued to visit more Yorkshire communities, spending some days in Sheffield where he talked with Ebenezer Elliot the well-known author of the "Corn Law Rhymes" and gained his support as well as the cooperation of the trade unions in Sheffield.

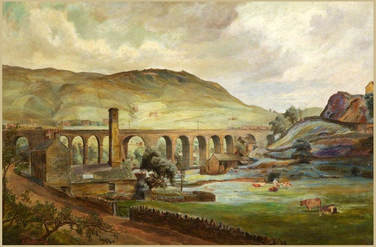

Saddleworth Viaduct, Edwin Bottomley [Courtesy ArtUK CC BY-NC-ND]

Saddleworth Viaduct, Edwin Bottomley [Courtesy ArtUK CC BY-NC-ND]

When Collins attended meetings held indoors due to weather conditions such as at Barnsley and Elland (June 14th 1838) the places were crowded to excess, and hundreds had to be turned away.

In those days, people were accustomed to walking considerable distances. Consequently, moorland locations offering large, open spaces and away from the authorities, were particularly popular places

(Katrina Navickas website http://protesthistory.org.uk/moors) for Chartist gatherings.

Saddleworth, where Collins attended a great outdoor meeting on 9th June 1838, was one such place with its sloping moorland, and gritstone built hamlets and villages. Here again, Collins appeared on the hustings alongside physical force advocate Feargus O'Conner the leader of the northern unions who issued his usual veiled innuendo of physical action when he said he supported the BPU National Petition so long as it would be the last one! (Northern Star 16 June 1838) Nevertheless John Collins held his own especially in the face of the extreme militant champion Joseph Stevens who said nothing could be done without physical force, and the only question was when should the people begin burning and destroying mills and property. Collins refuted such violent language and carried a vote for peaceful reform, and was clapped and cheered throughout his hour long speech.

In those days, people were accustomed to walking considerable distances. Consequently, moorland locations offering large, open spaces and away from the authorities, were particularly popular places

(Katrina Navickas website http://protesthistory.org.uk/moors) for Chartist gatherings.

Saddleworth, where Collins attended a great outdoor meeting on 9th June 1838, was one such place with its sloping moorland, and gritstone built hamlets and villages. Here again, Collins appeared on the hustings alongside physical force advocate Feargus O'Conner the leader of the northern unions who issued his usual veiled innuendo of physical action when he said he supported the BPU National Petition so long as it would be the last one! (Northern Star 16 June 1838) Nevertheless John Collins held his own especially in the face of the extreme militant champion Joseph Stevens who said nothing could be done without physical force, and the only question was when should the people begin burning and destroying mills and property. Collins refuted such violent language and carried a vote for peaceful reform, and was clapped and cheered throughout his hour long speech.

VOTE OF THANKS FOR THE RETURNING HERO

The regular Tuesday meeting of the Birmingham Political Union on 26th June 1838 was unusually crowded. John Collins was present, having just returned from his tour of duty in Scotland and the North. He was clearly fatigued and had not seen his family for many weeks. There was miscellaneous discussion on whether or not to celebrate Queen Victoria's coronation. Then - almost like an afterthought - councilman Robert K Douglas addressed the meeting and said: "They would be the most cold-hearted, worthless and insensible set of beings, if they did not, with all their hearts, congratulate him (Collins) on his return." To which there was long and loud cheering from the assembled membership. Collins rose to his feet, and ever the self-effacing gentleman, he thanked the crowd, briefly spoke of his tour, and said his success in Scotland and the North was due to the people's confidence in the "men of Birmingham." His tribute to the "men of Birmingham" may well have been partly true, but it was John Collins more than anyone else who had helped merge Scotland and England in the new reform movement.

Apart from Douglas's peculiar turn of phrase, Collins and his great accomplishment had been mostly ignored by the Union leaders. They had excluded him from the Great Glasgow Demonstration that he had worked so hard to bring about. At a massive reception in Birmingham, got up by the BPU council before Collins had a chance to return from Scotland, the Union leaders took all the credit for Scotland's (and Collins') success. A few days after that, at a Union meeting, Douglas boasted of the council's celebrity status in Scotland and how the people asked Collins to secure their autographs! Later, at that same meeting, Douglas all but admitted the council's neglect of their friend John Collins, claiming it was nothing more than "forgetfulness." As Indira Gandhi said, "There are two kinds of people: those who do all the work, and those who take the credit for it." John Collins undoubtedly belonged to the first.

In any event, it was left to two lesser known Union men to properly set the record straight toward the end of that Union meeting on the 26th. A Mr Aaron called for a vote of thanks to Mr Collins for the manner in which he had discharged his duty. This resolution was seconded by a Mr Cutler who said that in considering the effects which had been produced, and knowing it was through Mr Collins' exertions, he was justly entitled to their warmest thanks. The resolution was accordingly carried amid much cheering and applause.

Apart from Douglas's peculiar turn of phrase, Collins and his great accomplishment had been mostly ignored by the Union leaders. They had excluded him from the Great Glasgow Demonstration that he had worked so hard to bring about. At a massive reception in Birmingham, got up by the BPU council before Collins had a chance to return from Scotland, the Union leaders took all the credit for Scotland's (and Collins') success. A few days after that, at a Union meeting, Douglas boasted of the council's celebrity status in Scotland and how the people asked Collins to secure their autographs! Later, at that same meeting, Douglas all but admitted the council's neglect of their friend John Collins, claiming it was nothing more than "forgetfulness." As Indira Gandhi said, "There are two kinds of people: those who do all the work, and those who take the credit for it." John Collins undoubtedly belonged to the first.

In any event, it was left to two lesser known Union men to properly set the record straight toward the end of that Union meeting on the 26th. A Mr Aaron called for a vote of thanks to Mr Collins for the manner in which he had discharged his duty. This resolution was seconded by a Mr Cutler who said that in considering the effects which had been produced, and knowing it was through Mr Collins' exertions, he was justly entitled to their warmest thanks. The resolution was accordingly carried amid much cheering and applause.

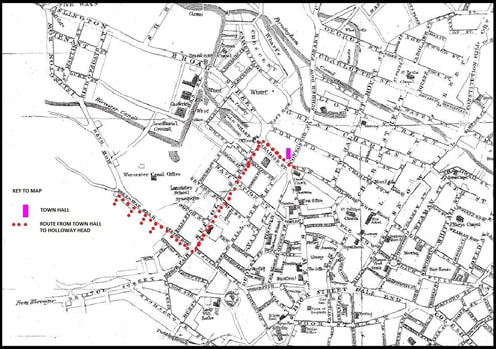

HOLLOWAY HEAD & THE BIRTH OF THE CHARTIST MOVEMENT

The Grand Midland Demonstration - 6th August 1838

|

An historic moment for the working class, and the country as a whole, was the so-called "birth" of the Chartist Movement (The Chartist Movement, Hovell p107) that took place when the people of Birmingham and surrounding districts met on 6 August 1838 for the Great Midland Demonstration at Holloway Head - yet another outdoor meeting place. Successful reform meetings in support of the National Petition earlier that year at Glasgow, Manchester and Newcastle, all attended by John Collins (Birmingham Political Union, Flick p143) and other important places provided the impetus and confidence previously lacking for the Birmingham Political Union to call for a grand kick-off demonstration on their home turf.

|

Various newspapers of the day reported a massive 200,000 to 250,000 individuals attended the Grand Midland Demonstration which began at the Town Hall in Birmingham. The speakers included the main players from the four hotbeds of reform: London and the South, Yorkshire and the North, Scotland, and last but not least Birmingham. In spite of their differences in strategy for gaining reform, the leaders from those places all came together at the Great Midland Demonstration.

The Purpose of the Grand Midland Demonstration

The main business of this great meeting was the:

- Approval and adoption of the BPU's National Petition,

- Election of Birmingham delegates to attend the first ever Chartist Convention,

- Approval for a "National Rent" to help pay for the Convention, and

- A call for other towns to follow suit.

The Purpose of the Grand Midland Demonstration

The main business of this great meeting was the:

- Approval and adoption of the BPU's National Petition,

- Election of Birmingham delegates to attend the first ever Chartist Convention,

- Approval for a "National Rent" to help pay for the Convention, and

- A call for other towns to follow suit.

John Collins Leads the Procession to Holloway Head

John Collins played a special part in the Grand Midland Demonstration. He and fellow BPU council member John Pierce were appointed Joint Marshalls, and charged with organizing and conducting arrangements for a huge procession from Birmingham Town Hall to Holloway Head.

|

The day began with a BPU meeting in the Town Hall, at which time John Collins (the only working man already on the council) was re-elected to serve in the forthcoming year. Other working men were additionally elected to serve on the council, some of whom would later aid in the downfall of the Union.

This was followed by a massive procession to Holloway Head which Collins and Pierce led on horseback through the streets of Birmingham. From the Town Hall the procession "set off at a brisk pace" heading down Suffolk Street, up Exeter Row (past the Dog & Duck), on up Holloway Head, and along the line of streets to the hustings in the fields at Holloway Head. |

The procession consisted seven divisions of men, with Birmingham in the lead, and the other six divisions each comprising several outlying towns. For instance the fourth division was made up of five nearby towns, one of which was Walsall with some 3,000 union men. It took about an hour from the time the first division set out from the Town Hall until the final division reached the crowds already assembled at Holloway Head.

John Collins certainly had a head for planning and organizing as was seen at this event and during his tour of agitation in Scotland.

The People Assemble at Holloway Head

|

Among the reported 250,000 crowd at Holloway Head, many women (or 'bonnets' as they were often called) were said to have attended the Grand Midland Demonstration. There were arrangements to accommodate the press, and a raised platform (or hustings as it was usually called) was erected for the speakers as well as two trumpeters "to give notice when silence was required." However, there was little or no disruption, and the trumpeters were never called on!

There were grandiose speeches by the leading reformers of the day, including some that dragged on. Like all top orators, including John Collins, they were masters at igniting and holding a crowd - and even though it would have been hard for everyone at the huge gathering to hear the speakers, the excitement and the reaction of those within hearing distance would have brought forth great rolls of applause and cheering. |

The Dog & Duck Public House (1800-1872c) on Holloway Head at the time of the Grand Midland Demonstration. Behind it was open farm land. The pub was located between Florence Street and Windmill Street which was named for the nearby windmill built by a Mr Chapman the century before. [Image courtesy Library of Birmingham - 19th century artist unknown]

|

Thomas Attwood presented the National Petition, the principles of which were outlined in The People's Charter. Joshua Scholefield (Member of Parliament for Birmingham) talked of the failure of the Great Reform Bill and how a mere 4,000 were eligible to vote for Birmingham's two Members of Parliament. Fergus O'Connor summed up the whole when he told the great crowd "he recognized the meeting as the signing, sealing, and delivering of the great moral covenant which was this day entered into among the people."

John Collins' Speech at the Grand Midland Demonstration

|

In comparison with the other leading speakers, John Collins' speech was relatively short and to the point. He said he would not dwell on the misdeeds of the Whigs and Tories, or the sad state of affairs which everyone knew all too well when they looked in the faces of their starving children.

He said it was no child's play they were engaged in, no subject to be trifled with, but that it involved what was best for the country as a whole and ultimately the destinies of Europe. He told the cheering crowd he was confident in their support, and there was no doubt of their success so long as they stuck together.

Unfortunately, in one respect, Collins' speech eerily predicted the government's eventual clampdown on the Chartist Movement when he warned that Delegates (elected to represent the people at the National Convention) were at risk for reprisals. He called on the people to stand by their Delegates, to which the crowd responded with cries of "We will." To which Collins added if he were to become a victim, it would not stop him declaring his duty to the cause.

|

Oh, how true this would be! In 1839-1840 hundreds of Chartist leaders (including John Collins) were arrested and imprisoned.

Approval of Delegates & National Rent

|

In addition to speeches promoting the National Petition and political reform, the people attending the Grand Midland Demonstration were asked to approve a Resolution appointing Delegates to attend the first ever Chartist Convention, to be held in London the following year.

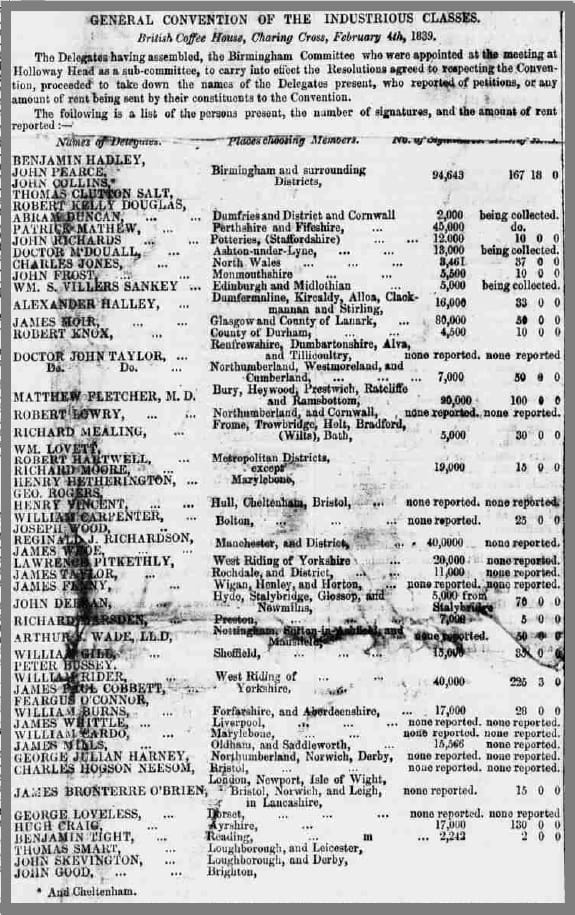

John Collins and several other BPU leaders were elected Delegates to represent the people of Birmingham. The Resolution stated the General Convention of the Industrious Classes should not exceed forty-nine in number, since more than that made it illegal. Essentially, the purpose of the Convention was the organization and delivery of the National Petition into law. Resolution was also passed in support of a National Rent to help fund not only the Convention in London, but also to pay those Delegates who went out on lecture tours promoting the new reform movement. |

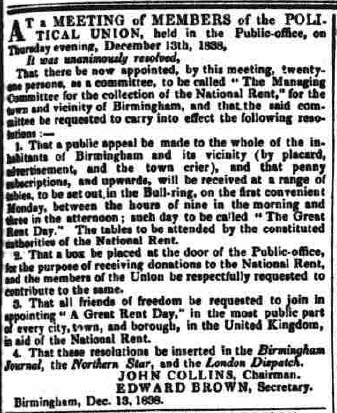

Later in the year (13th December 1838) in opposition to the middle class leaders of the BPU, John Collins and fellow Union councilman Henry Watson formed a Managing Committee for the collection of "rent" or funds to support the BPU's agitation efforts. John Collins chaired that Committee which met on Thursdays. [Chartist Crisis in Birmingham, Tholfsen] It was a sign of a split between the upper and lower orders of the Union leadership.

|

COLLINS - DELEGATE FOR OTHER TOWNS

As Collins traveled to other towns throughout the Midlands and elsewhere, his popularity as a Birmingham leader increased.

In addition to representing Birmingham, he was elected Delegate for Northampton (elected 20 May 1839), Coventry and Cheltenham (elected 24 Jan 1839). [History of the Chartist Movement, J West] |

APPROVAL FOR THE NATIONAL PETITION

The National Petition in favour of the People's Charter was wholeheartedly adopted at the Great Midland Demonstration, and as Alfred Langton put it in his book A Century of Birmingham Life: A Chronicle of Local Events from 1741-1841: ".. .. the strength of Chartism in Birmingham is proved by the fact that no fewer than 94,634 signatures were appended to it in this town. They adopted the Union cry of the Bill, the whole Bill, and nothing but the Bill, and were for the Charter, the whole Charter, and nothing but the Charter."

Or, as John Collins succinctly put it in his speech to the thousands at Holloway Head: "To retract, to retreat, is, at this time, absolutely impossible......"

To read more about the Great Midland Demonstration and Holloway Head please click here.

Or, as John Collins succinctly put it in his speech to the thousands at Holloway Head: "To retract, to retreat, is, at this time, absolutely impossible......"

To read more about the Great Midland Demonstration and Holloway Head please click here.

CHARTISM'S MORAL FORCE

Physical force men used threatening verbiage such as down with the throne and burn the church! Fergus O'Connor was heard to hint at revolution and his fiery associate Joseph Stephens said there were thousands of guns being held in storage. Even though this kind of "treasonous" talk was at odds with the moderates' preference for milder language, the two factions would frequently appear on the same platform (also known as the "hustings") galvanizing the crowds in support of the National Petition and the People's Charter.

Moral force advocate John Collins was invariably in the mix - holding his own and encouraging reform through peaceful means. Such was the case at the three famed working class meetings at Kersal Moor, Liverpool, and Hartshead Moor that followed on the heels of the Grand Midland Demonstration. For more about Physical Force and Moral Force please click here.

Moral force advocate John Collins was invariably in the mix - holding his own and encouraging reform through peaceful means. Such was the case at the three famed working class meetings at Kersal Moor, Liverpool, and Hartshead Moor that followed on the heels of the Grand Midland Demonstration. For more about Physical Force and Moral Force please click here.

Kersal Moor - 24 September 1838

|

In spite of a veritable downpour and a four mile walk from Manchester (not to mention banners with threatening words and symbols) the Kersal meeting on the Lancashire moorland was as orderly and successful as the Grand Midland Demonstration in Birmingham. Factories were closed and people poured in from virtually every village in the Lancashire district.

Both sides of the Chartist aisle were in attendance with John Collins (as a moral force man) joining O'Connor and Stephens (physical force men) and several other speakers from major towns including London and Newcastle. |

Resolution in support of the Charter was overwhelmingly approved by a crowd of 250,000 (Times newspaper report) or 300,000 (Rosenblatt). Here too, as at the Grand Midland Demonstration in Birmingham, delegates were elected to attend the first Chartist Convention to be held in London the following year.

Maritime Town of Liverpool - 25 September 1838

|

The meeting at the Merseyside town of Liverpool, though apparently not as well attended as Kersal Moor, was well represented by all factions and viewpoints, including a little additional excitement when some rogue speaker interrupted proceedings and attempted to throw the whole into disarray.

Here again, John Collins stood on the platform alongside the likes of O'Connor, Bussey, Lowry, and Cobbett. Collins' speech on universal suffrage and the enormous support of the Birmingham people brought forth much cheering from the crowd gathered on the Old Infirmary Grounds near the Railway Station on Lime Street in Liverpool. |

This was followed by a dinner at the Queens Theatre in Liverpool. The top table included our man Collins and the other speakers, overlooking some two hundred guests. Thomas Attwood did not attend the Liverpool or Manchester meetings.

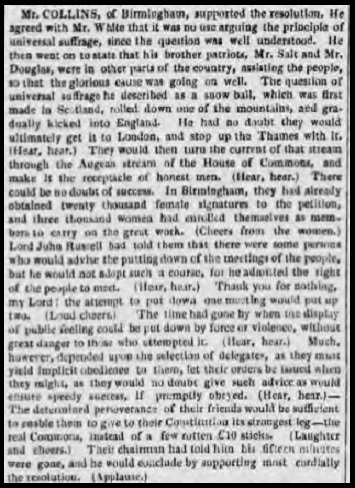

Hartshead Moor at Peep Green - 15 October 1838

|

Hartshead Moor (later known as Peep Green) in the West Riding of Yorkshire was the site of yet another huge Chartist meeting. As to be expected there was a plethora of top Yorkshire speakers (O'Connor, Pitkeithly, Stephens, Bussey and White) and more. Many of them talked-up the use of physical force if needed, and Stephens actually advised arming, and he said there were 5,000 armed in his district.

John Collins (the lone representative from Birmingham) and John Fielden the radical Member of Parliament for Oldham, Yorkshire both called for caution and peaceful means to obtain reform, but they were easily outnumbered by the militants of the North. During the course of this meeting Fergus O'Connor and other Delegates were elected to represent the West Riding of Yorkshire at the 1839 National Convention in London. Like many such 'monster' meetings the numbers in attendance varied depending on Chartist propaganda and newspaper bias. Estimates for Peep Green were anywhere between 30,000 and 300,000! A letter in the Northern Star dated 16th October 1838 put it at even more. Nevertheless, support for the National Petition and the People's Charter was gaining momentum. |

|

In his speech at Hartshead Moor, Collins likened the momentum to " .... a snowball which was first made in Scotland, rolled down one of the mountains, and gradually kicked into England. He had no doubt they would get it to London ..."

Collins talked of the support of the women of Birmingham, who had signed the National Petition and enrolled in their own union. He also referred to the "few rotten £10 sticks " casting aspersions on the House of Commons (the elected body of Parliament) and the middle class voters who qualified for the franchise (under the Reform Act of 1832) through property valued at £10 a year. The 1832 Reform Bill (or Great Reform Bill as it was known) extended the vote to the middle classes. It benefited the middle class leaders of the Birmingham Political Union but did nothing for the mass of working men they supposedly represented. |

Hartshead Moor at Peep Green, West Riding of Yorkshire. Such open places were much favoured by the Chartist Movement, providing space for large crowds away from the watchful eye of the authorities. In those days people were used to walking long distances.

|

BACK TO THE MIDLANDS

The BPU's plan of agitation in Scotland and North was highly successful, largely thanks to John Collins' judicious efforts and his willingness to appear at the same demonstrations as Fergus O'Connor and his militant supporters. Collins traveled hundreds of miles during his tour, attending as many as three meetings a day, during which time the BPU council was content to sit back and await results.

When Collins returned to Birmingham with "mild praise" for the northern organizers in Yorkshire his remarks did not go down well with the council's middle class leaders. Not for the first time the middle class Union leaders were unwilling to acknowledging Collins' or anyone else's success as was seen when they left him out of the Great Glasgow Demonstration back in May. It was that kind of "aristocratic attitude" toward the working class that added to the demise of the BPU the following year.

When Collins returned to Birmingham with "mild praise" for the northern organizers in Yorkshire his remarks did not go down well with the council's middle class leaders. Not for the first time the middle class Union leaders were unwilling to acknowledging Collins' or anyone else's success as was seen when they left him out of the Great Glasgow Demonstration back in May. It was that kind of "aristocratic attitude" toward the working class that added to the demise of the BPU the following year.

|

Even so, John Collins commenced regional campaign efforts. On 11 August 1838 at a meeting called by the local town-crier Collins appeared at the Sea Lion Inn, High Street, Hanley in Staffordshire, which resulted in the formation of the Potteries Political Union and their support for the National Petition at a massive demonstration later that year. At Bristol he was once again on the platform with Fergus O'Connor, and at a meeting in Cheltenham John Collins was referred to as one of the apostles of the Chartist Movement.

|

TENSIONS RISE BETWEEN 'WARING GROUPS'

Moral vs Physical Force

As the year 1838 progressed, animosity grew between the Birmingham Political Union and Fergus O'Connor the leader of the Northern Unions. Each had their own approach to gain reform, and each was critical of the others' tactics. The (moral force) BPU council leaders were accused of being old women, the (physical force) northern leader was condemned for his fighting talk, and both sides jockeyed for control of the reform movement.

As the year 1838 progressed, animosity grew between the Birmingham Political Union and Fergus O'Connor the leader of the Northern Unions. Each had their own approach to gain reform, and each was critical of the others' tactics. The (moral force) BPU council leaders were accused of being old women, the (physical force) northern leader was condemned for his fighting talk, and both sides jockeyed for control of the reform movement.

Middle vs Working Class

Within the Birmingham Political Union itself working class men were equally at odds with its middle class leadership. The fact that middle class men were in charge of a working man's cause no longer sat well with the lower orders: one working class man newly elected to the council of the BPU complained bitterly that its middle class leaders ignored him; and Attwood somewhat disparagingly referred to the Union's working class members as his "Brummagem buttons."

Within the Birmingham Political Union itself working class men were equally at odds with its middle class leadership. The fact that middle class men were in charge of a working man's cause no longer sat well with the lower orders: one working class man newly elected to the council of the BPU complained bitterly that its middle class leaders ignored him; and Attwood somewhat disparagingly referred to the Union's working class members as his "Brummagem buttons."

|

At a crowded Union meeting on 9th April 1839, Thomas Salt, one of the middle class leaders of the BPU, said the campaign which John Collins had conducted in Scotland had been a total failure. [Birmingham Journal 13 April] The real truth of it was John Collins had been highly successful in motivating the Scots to support the National Petition and join the rising Chartist Movement, so much so that at the end of Collins' tour (even before he returned home to Birmingham) the middle class leaders of the BPU very loudly claimed credit for Scotland's success.

|

Little wonder then, long after the demise of the BPU, John Collins publicly declared the day was done when any middle class man could dictate to the working class, and any future alliance between the two must be based on the principal of equality (Birmingham Journal 13 March 1841).

John Collins into the Breach

Meanwhile, on Tuesday 13 November 1838 the BPU's weekly public meeting was virtually shanghaied by the sudden appearance of Fergus O'Connor who had come to defend his reputation as a physical force advocate. There followed an altercation during which John Collins, ever the voice of moderation, forcibly told O'Connor that setting an ultimatum for approval of the National Petition was not O'Connor's to make, and that this was an issue for the General Convention of the Industrious Classes. Surprisingly, O'Connor backed down before an audience of some 3,000 in which he acquiesced to Collins' wishes, only to return to Birmingham a week later on 20th November for yet another attempted showdown. However, once again John Collins stepped in and helped smooth things over between O'Connor and the BPU's middle class hierarchy.

Meanwhile, on Tuesday 13 November 1838 the BPU's weekly public meeting was virtually shanghaied by the sudden appearance of Fergus O'Connor who had come to defend his reputation as a physical force advocate. There followed an altercation during which John Collins, ever the voice of moderation, forcibly told O'Connor that setting an ultimatum for approval of the National Petition was not O'Connor's to make, and that this was an issue for the General Convention of the Industrious Classes. Surprisingly, O'Connor backed down before an audience of some 3,000 in which he acquiesced to Collins' wishes, only to return to Birmingham a week later on 20th November for yet another attempted showdown. However, once again John Collins stepped in and helped smooth things over between O'Connor and the BPU's middle class hierarchy.

|

National Rent Committee

In December 1838 John Collins was officially in charge of the Managing Committee for collecting 'National Rent' or funds on behalf of the Birmingham Political Union. National Rent was used to support the activities of the Union, including the Birmingham Delegates elected to attend the General Convention of the Industrious Classes. In essence the Managing Committee was a breakaway working class group that resented the BPU's middle class leadership. |

It was a sign of things to come, and by the time the Chartist Delegates met at the General Convention of the Industrious Classes in London early next year the scene was set for major confrontation between the waring sides.

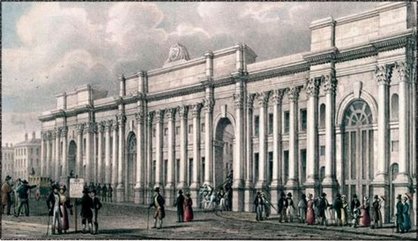

GENERAL CONVENTION OF THE INDUSTRIOUS CLASSES

(British Library Collection) https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/grand-architectural-panorama-of-london

DELEGATES REPRESENT THE PEOPLE OF BIRMINGAM

At the Great Midland Demonstration held in Birmingham on 6th August of 1838, several of the middle class leaders of the Birmingham Political Union were formally elected to attend the General Convention of the Industrious Classes to be held in London the following year. These "Delegates" represented the working class of Birmingham, except that of the five elected only one, “John Collins (Sunday-school teacher)” belonged to that class. He also represented Northampton, Cheltenham and Coventry having been officially elected at public meetings in those towns. Collins was also chairman of the Rent Committee that raised the money to support the Birmingham Delegates.

DELEGATES ASSEMBLE IN LONDON

Collins Does Not Give Up

John Collins, however, was not one of those who resigned from the Convention. Like Douglas, Salt and Hadley he objected to ultimatums and threats of force to obtain reforms. Additionally, he considered "ulterior measures" and a move to Birmingham where they would be safer from London reprisals were beyond the purview of the Conference [The Lion of Freedom, James Epstein p 133-134]. Nevertheless, unlike his middle class colleagues - who were basically in a power struggle with the militant leader, Fergus O'Connor - John Collins did not jump ship. At one point he even expressed surprise at the absence of Delegates, but ever a diplomat and a sensible man, Collins stayed the course and continued to advocate non-violent words and deeds. For more about the General Convention and John Collins involvement please click here.

John Collins, however, was not one of those who resigned from the Convention. Like Douglas, Salt and Hadley he objected to ultimatums and threats of force to obtain reforms. Additionally, he considered "ulterior measures" and a move to Birmingham where they would be safer from London reprisals were beyond the purview of the Conference [The Lion of Freedom, James Epstein p 133-134]. Nevertheless, unlike his middle class colleagues - who were basically in a power struggle with the militant leader, Fergus O'Connor - John Collins did not jump ship. At one point he even expressed surprise at the absence of Delegates, but ever a diplomat and a sensible man, Collins stayed the course and continued to advocate non-violent words and deeds. For more about the General Convention and John Collins involvement please click here.

THE NATIONAL PETITION IS READY

After three months of meetings, campaigning, and preparing signatures John Collins (as a member of the Petition Committee) reported to the Convention "he had redeemed his pledge" the National Petition was ready. Thomas Attwood, Member of Parliament for Birmingham agreed to present the Petition to Parliament on the responsibility that John Collins would bring it to him. On 7th May the signed petition sheets (stitched together in a long, wide strip and rolled up like a carpet about 9 feet in circumference) were transported in a horse drawn cart, draped in the Union Jack, to Attwood at an address in Panton Square. The Petition was escorted by William Lovett, John Collins, Henry Vincent, Fergus O'Connor and other Convention delegates walking two by two in procession through the streets of London.

In view of its incredible size, Attwood wanted to know if the Petition should be pushed in a wheel barrow into the House of Commons! Collins replied it was too heavy (500lbs) for a wheel barrow, and that the last time he measured the Petition it was two miles and 1,504 yards - almost 3 miles long. Collins also said he would provide a list of towns, hamlets and villages that had signed the Petition and that it contained over one and a quarter million signatures.

In view of its incredible size, Attwood wanted to know if the Petition should be pushed in a wheel barrow into the House of Commons! Collins replied it was too heavy (500lbs) for a wheel barrow, and that the last time he measured the Petition it was two miles and 1,504 yards - almost 3 miles long. Collins also said he would provide a list of towns, hamlets and villages that had signed the Petition and that it contained over one and a quarter million signatures.

THE CONVENTION DECAMPS TO BIRMINGHAM

Immediately after the Petition was delivered to Thomas Attwood the delegates voted to leave London and relocate to Birmingham. Once there the Convention took a few weeks' hiatus whilst John Collins and other Delegates continued their campaign efforts in Scotland and the North. See Collin's letter of appointment signed by William Lovett.

Miltant Chartist Leaders Cause Trouble

When the delegates returned to Birmingham for the reopening of the Convention at the beginning of July 1839 the town was in a state of high excitement awaiting the outcome of National Petition which was due to be presented to Parliament on 12 July. Thousands of people collected in the Bull Ring on a daily basis. There had been incendiary and reckless speeches for many weeks by militant working men which resulted in arrests (Edward Brown, of the Convention, was one of them). The Birmingham authorities declared a ban on public assembly, and on one occasion the Mayor of Birmingham contacted John Collins and asked him to do what he could to keep things peaceable, which Collins had done so according to the Mayor. However, the noisy meetings continued and increased, and on the first day of July Fergus O'Connor the Northern radical prone to inflammatory and overstated speeches encouraged still further unrest by proclaiming before the crowd at Gosta Green, Birmingham that he had come to provide them with his protection from the armed authorities. Small wonder then, the local Magistrates called on London police to help enforce the ban on public meetings.

Miltant Chartist Leaders Cause Trouble

When the delegates returned to Birmingham for the reopening of the Convention at the beginning of July 1839 the town was in a state of high excitement awaiting the outcome of National Petition which was due to be presented to Parliament on 12 July. Thousands of people collected in the Bull Ring on a daily basis. There had been incendiary and reckless speeches for many weeks by militant working men which resulted in arrests (Edward Brown, of the Convention, was one of them). The Birmingham authorities declared a ban on public assembly, and on one occasion the Mayor of Birmingham contacted John Collins and asked him to do what he could to keep things peaceable, which Collins had done so according to the Mayor. However, the noisy meetings continued and increased, and on the first day of July Fergus O'Connor the Northern radical prone to inflammatory and overstated speeches encouraged still further unrest by proclaiming before the crowd at Gosta Green, Birmingham that he had come to provide them with his protection from the armed authorities. Small wonder then, the local Magistrates called on London police to help enforce the ban on public meetings.

|

On 4th July a "posse" of 60 London police suddenly arrived on the scene, and in their attempts to disperse the crowds in the Bull Ring a riot broke out. Many were hurt and injured. The Convention met the next day and issued a set of Resolutions that condemned the actions of the police and local authorities.

William Lovett, signed the Resolutions, and John Collins, who had chaired the meeting, took the Resolutions to a local printer and arranged for a Bill Sticker to post copies of them all over the town. As a result Lovett and Collins were arrested and imprisoned for libel and sedition. The irony of it was that two of the most moderately voiced, non-violent men in the Chartist Movement paid the price for the violent rhetoric of Fergus O'Connor and other rabble rousing militants. |

Navigation Tips:

- Use the Menu Bar at top of each Page to follow the John Collins' story in chronological order.

- Go to the Content Page to browse all the Pages on the entire website.

- The Welcome Page gives an overview of the life and times of John Collins. I recommend you start there.

- The purple button will take you to the top of this Page.

Proudly powered by Weebly